Saturday, April 29, 2006

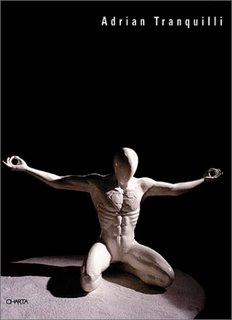

Adrian Tranquilli

Adrian Tranquilli is a young artist currently residing in Rome who is producing interesting sculptures with superhero subjects and themes. In December of 2005 the Mimmo Scognamiglio Arte Contemporanea in Naples mounted an exhibit of Tranquilli's work titled "The Age of Chance."

Cathryn Drake has a review of the show in the May 2006 issue of Artforum magazine. (Unfortunately, it's not [yet] available online.)

Here's an extended excerpt:

For some time, Adrian Tranquilli has been portraying superheroes as poignantly human. In this show ... a pure white Superman--the original superhero--bursts robustly out of the wall with stigmata of gold bleeding from between his ribs (This is Not a Love Song 1, all works 2006), a phantom of spiritual purity. Spiderman's form half emerged out of another wall (This is Not a Love Song 2), regarding the upturned palm of his hand, from which a stream of white gold spilled into drops on the floor. And isn't Christ himself a sort of superhero? In an earlier work, Tranquilli confounded the Savior's identity with that of Batman: his sculpture Batman: The Dark Knight, Vatican City, 1998, depicts a crucified Jesus with the Batman symbol emblazoned across his chest. ...

The religious analogy is simplistic yet fundamental, carrying with it implications of our need to reflect our own identity in our icons as well as to seek guidance from a savior. Hero myths date back to the beginning of civilization, but the superhero genre emerged in tandem with American modernism, springing from our collective need to create order out of the chaos of world wars and revolutionary social changes. Superheroes highlight the difference between good and evil, comforting us through identification with their extraordinary powers and ability to overcome their nemeses. Sacrificing their personal lives to save the world, they must keep their identities secret. ...

What would happen if everybody were a superhero? As the identities of our icons become closer to our own, we might have to become our own saviors. ... Indeed, by literally merging the identities of pop and religious icons--and bringing them down to earth--Tranquilli's precious sculptural objects seem to be drained of their power, passion, and significance. Like a child who refuses to take off his superhero costume long after Halloween, Tranquilli may have finally taken the concept to the point of banality.

Friday, April 28, 2006

Ready, Set, Go!

There's a fascinating interview up at Newsarama with Dr. Naif al-Mutawa, CEO of Teshkeel Media Group, the publisher of the upcoming comic title The 99.

Some choice excerpts:

As detailed with the preview, the concept of The 99 is based on the 99 attributes of God in Islam. Many of these names refer to characteristics that can be possessed by human individuals. For example - generosity, strength, faithfulness, and wisdom are all virtues encouraged by a number of faiths.

Members of The 99 are ordinary teenagers and adults from across the globe, who each come into possession of one of the 99 mystical Noor Stones and find themselves empowered in a specific manner. Dilemmas faced by The 99 will be overcome through the combined powers of three or more members. Through this, The 99 series aims to promote values such as cooperation and unity throughout the Islamic world. Although the series is not religious, it aims to communicate Islamic virtues, which are universal in nature.

...

NRAMA: But still, as you’ve explained it, that was something of the source of this – of what you’re looking to accomplish through The 99 – to try and conquer the almost nihilistic view of the future that can serve as the impetus to push them toward more militant forms of opposition, wasn’t it?

NA-M: Exactly. That part of the world is kind of in an intellectual purgatory. Some things are taboo because they are coming from the outside, and therefore cannot be incorporated into long-held beliefs, and meanwhile, the materials that are coming from the inside is coming from people who were selected through negative selection. The people who end up wearing scowls all the time, and the people who we here in the United States see as shouting about fire and brimstone and the end of the world – the equivalent of those people are dictating content.

The idea was multi-fold – they don’t want Westernization, fine. But at the same time, we cannot afford to allow these people to set the agenda. We – me and others – have to step up.

...

[W]e have 99 characters, half male, half female, which, to my mind represents the pluralistic, multicultural community that was present in the Golden Age of Islam. And you know what? Some of the female characters will have more “masculine” aspects given to them. The girl from Portugal will be one of the physically strongest of them all, for example. This is not about stereotypes. Of the half that are female characters, five or six will cover their hair, and do it in a way that reflects their individual cultures.

We have one character, Batina, whose attribute is “The Hidden,” so she’ll wear the cover from top to bottom. The other 30-plus female characters will show their hair. Because as much as some would like you to believe that there is only one way to interpret that law, there isn’t.

NRAMA: But again, no religion or mentions of the Qu’ran?

NA-M: Nothing. Not a Qu’aan, no prayer, nothing.

Man, that's a fascinating interview, well worth reading in its entirety.

When I first read about this project, my immediate thought was, how can I possibly get my hands on copies of this title? Well, it seems that the answer is almost at hand; I saved the choicest information from the Newsarama piece for last: Teshkeel is in active negotiations for a US distribution deal and hope to announce something soon.

In the meantime, those of you as excited by this as I am can get more information at The 99 website, which provides bios of selected characters, as well as information on the creators, the publisher, and his company.

I ask you: how can one not like a comic that's got as one of its heroes a young woman named Mumita the Destroyer?

Thursday, April 27, 2006

More 80s Love

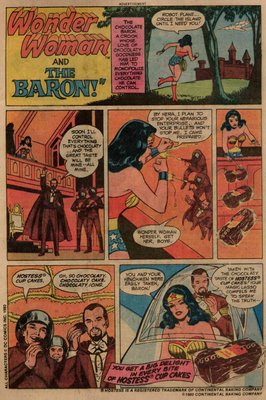

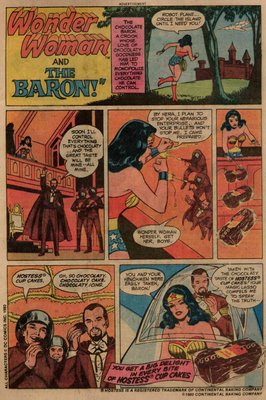

The Dreaded Chocolate Baron

From The New Adventures of Superboy #12, December 1980.

Though I don't need anyone to explain the bullet-stopping bracelets to me, I have no idea where those Cupcakes Diana is tossing around actually came from.

Stored in the castle to begin with? Dropped from the invisible robot plane?

(This scan can also go in Tom Spurgeon's Comics Made Me Fat file.)

Aficionados take note: this entry at Drawn! directed me to the Hostess Cakes advertisement motherlode: Seanbaby's Hostess Page.

From The New Adventures of Superboy #12, December 1980.

Though I don't need anyone to explain the bullet-stopping bracelets to me, I have no idea where those Cupcakes Diana is tossing around actually came from.

Stored in the castle to begin with? Dropped from the invisible robot plane?

(This scan can also go in Tom Spurgeon's Comics Made Me Fat file.)

Aficionados take note: this entry at Drawn! directed me to the Hostess Cakes advertisement motherlode: Seanbaby's Hostess Page.

Spoilerless Praise

Just when I had grumpily convinced myself that Infinite Crisis #7 would probably disappoint me rather than anything else, Gail Simone's Villains United Infinite Crisis Special appeared in my comic store, and reading it has turned everything around for me.

The book has single-handedly rekindled my interest in the entire endeavor.

Good comics work in the same way that good movies, novels, and oral story-telling work: VU is masterfully paced and plotted, the characterizations are spot-on, and GS displays a very nice sense of timing.

On the last point, I'm not just talking about a big reveal in the final pages (though there is one), but rather the careful way in which a good writer will choose exactly when and how to feed us the information, character moments, and plot developments that comprise her narrative.

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

Godard, Again

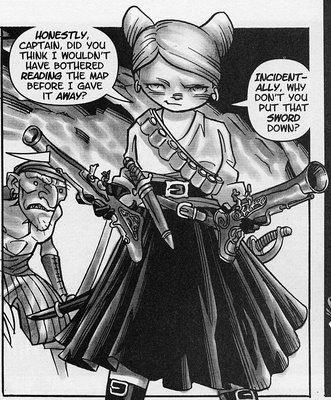

All you need to make a film is a girl and a gun.--Jean-Luc Godard.This works for comics, too.

(And girl is appropriate, in this case.)

If you're looking for a good read, I definitely recommend Ted Naifeh's Polly and the Pirates, published by Oni Press. (The image is from issue #5, released today.)

Naifeh's comic has disappointed me only in being finite; it's a six issue limited series.

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

Spider-Girl News

Inklings that perhaps Spider-Girl will continue to exist in some form beyond issue #100, via Newsarama.

#100 - NOT THE END? SPIDER-GIRL CONTINUES? by Matt Brady

Though Marvel has announced – multiple times – that Spider-Girl will end with July’s issue #100, this weekend at the Pittsburgh Comic-Con, writer Tom Defalco and artist Ron Frenz strongly hinted that, as with many things at Marvel, dead may not mean dead.

According to the series’ creators, there is a possibility of a relaunch of a Spider-Girl series, or a series starring Spider-Girl in the future. As the two revealed at a Spider-Girl panel, Defalco has begun preliminary discussions with Marvel about a relaunched title – which would feature a new logo and a more prominent role for Spider-Girl’s father (Peter Parker) in the series. Discussions are, Defalco stressed, preliminary at this point, with a new series not a done deal.

The series, which is Marvel’s longest-running comic in its history with a female protagonist, has been plagued since its earliest days with rumors and threats of cancellation. Set in a possible future of the Marvel Universe, the series stars May “Mayday” Parker, taking up her father’s mantle, as one of a new generation of Marvel heroes. Initially launched as part of a group of “MC2” titles that were set in the future world, Spider-Girl outlasted all of her contemporaries, running from 1998 to this year’s #100.

While the series made sense at its start (Marvel was expanding and looking for new territory to mine and attract readers), the series became somewhat marginalized over time as the other MC2 series fell by the wayside, and Marvel opted to focus on strengthening its “core” universe, and streamline its continuity.

Throughout the series run, it has been saved from cancellation time and time again by the efforts of its fans, who are, while not great in number, perhaps the most dedicated and loyal in mainstream comics. It was partly due to fan support that Marvel chose to collect and reprint Spider-Girl issues in digest form, which have reportedly proven to be very popular.

Asked for comment or confirmation about Defalco’s claims that a new Spider-Girl series is in the offing, a Marvel spokesperson said that nothing has changed - issue #100 is to be the final issue of the series. Asked for further clarification or if there was semantics issues involved, Marvel again reiterated that Spider-Girl #100 will be the final issue of the series.

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Art and Comics

When I first looked at this beautiful panel from All Star Superman #3, pencilled by Frank Quitely, I thought of Sandro Boticelli's Birth of Venus.

I don't know if Quitely has a fondness for Italian renaissance painting, or if the visual citation is even a conscious one. However, given the issue's multiple classical references, and Lois' central role in it as an object of desire, the connection to the painting does indeed seem appropriate.

Friday, April 21, 2006

Fears Allayed

Newsarama has posted an interview with Terry Dodson, in which he talks about pencilling the new Wonder Woman.

Allan Heinberg, the writer on the book, made some comments in an earlier interview which made me fear that perhaps the title might descend into unrelenting cheesecakery. I'm pleased to say that my concern has pretty much been dispelled by Dodson's description of how he is approaching the character.

Choice excerpts:

TD: The things I really went for were strength and beauty. Attractive. Powerful. Noble. Godlike. Yet, we want to show her being human too, because you can come across kind of cold with those other aspects played up. Something we’re trying to avoid is making her overtly sexy. We wanted her attractive, but not overtly sexy.

Something that I’ve worked out costume-wise in that regard is making her briefs not as brief, taking them away from the high-rise bikini to more of a brief. I’ve also made the part of her upper costume, which covers her chest, larger, and I’ve made the symbol across her chest bigger to cover up more over her cleavage. All of those I did because she’s a noble person, but she is walking around in a very small outfit, so it has to be balanced. It’s just minor things, but I’d like to think that there’s a little more sense of her nobility coming through because of them.

Also, something else I want to on occasion is to put a cape on her. I think that’s a really good look for her. It gets clumsy when she’s fighting, but for public appearances, I think it really gives her a regal look. That and giving her more hair, because when the cape isn’t there, her hair can act like a cape. It won’t be a ridiculous length, but as a design element, to make sure it has some of the same effect that a cape has. It also covers her up a little bit.

Those little things, I think, will help make a difference.

NRAMA: Speaking of the minor changes you’re making, while Wonder Woman has nobility and a regal nature, she’s also wearing, effectively, a bathing suit everywhere, which seems to come across as a contradiction. However, she has to wear it, given her status as a licensable property and corporate symbol. Do the two sides of that coin ever strike you when you’re drawing her, that is, “make her noble, regal, powerful, and a role model for girls and women, but put her in a bathing suit”?

TD: You do what you can. Basically, as you said, Wonder Woman is a corporate entity, so you can only make so many changes, and there are certain things that you’re tied to. So you adapt and work with what you can. A lot of it too, can be dealt with by poses and angles. It’s the way you chose to portray the character – even if she’s not wearing a lot of stuff, you can at least portray her in ways that are much more appealing to people. As an artist, you may be stuck with the outfit, but that doesn’t mean good taste doesn’t enter into the equation. There are ways to do it, and portray it in a way that conveys the positive aspects of the character without giving in to the…dark side.

You just have to remember who you’re drawing and what she’s all about, and come into it with a healthy respect for the character. It’s so easy to go cheesecake and overtly sexy – but you can draw beautiful and powerful without [being] overtly sexual.

I Love the 80s

They Knew How to Make Ads, Then

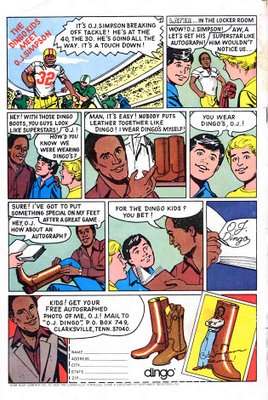

I found 6 or so issues of The New Adventures of Superboy from the early 80s in the 25c bin at my comic store. (The only way I could explain this was that the direction taken by Infinite Crisis must have driven some crestfallen Superboy fan to distraction.)

As yet I've only read the ads, and, in addition to several of those Hostess Cakes pages which depict superheroes capturing villains distracted by the orgasmic goodness of twinkies and cup cakes, this priceless OJ Simpson endorsement was in evidence.

Dingo kids?

I found 6 or so issues of The New Adventures of Superboy from the early 80s in the 25c bin at my comic store. (The only way I could explain this was that the direction taken by Infinite Crisis must have driven some crestfallen Superboy fan to distraction.)

As yet I've only read the ads, and, in addition to several of those Hostess Cakes pages which depict superheroes capturing villains distracted by the orgasmic goodness of twinkies and cup cakes, this priceless OJ Simpson endorsement was in evidence.

Dingo kids?

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

It's That Time Again

It's Miller Time.

For the Now It's Personal file: Frank Miller's variant cover to All Star Batman and Robin, The Boy Wonder #5. (Via Newsarama.)

As far as I can tell, this image hasn't been cropped, or re-sized.

I'm hoping that Jim Lee will provide a few panels within the book that actually show us Wonder Woman's face, in addition to her well-proportioned Amazonian backside.

For the Now It's Personal file: Frank Miller's variant cover to All Star Batman and Robin, The Boy Wonder #5. (Via Newsarama.)

As far as I can tell, this image hasn't been cropped, or re-sized.

I'm hoping that Jim Lee will provide a few panels within the book that actually show us Wonder Woman's face, in addition to her well-proportioned Amazonian backside.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Weaker? II

Uncle Junior: What are you looking at?

Bobby "Bacala" Baccalieri: I'm in awe of you.--From The Sopranos.

Juanita Wilson, injured in Iraq, August, 2004.

Recommended reading:

— Donna St. George, "Women Vets Refuse 'Victim' Label," Washington Post, 18 April 2006.

— Dave Moniz, "More Women Bear Wounds of War," USA Today, 5 May 2005.

Dawn Halfaker, injured June 2004.

The photos are from the Honolulu Advertiser, which reprinted Moniz's USA Today article.

Monday, April 17, 2006

Godard, Revised

All you need to make a film is a girl and a gun.--Jean-Luc Godard.

I'd change two words from that quote, replacing film and girl with comic and woman.

From Rex Libris #3, in which Circe (yes, that Circe) has got the reference desk covered; the librarians are impeccably (combat) trained; and the vandals, in fact, are Vandals.

Sunday, April 16, 2006

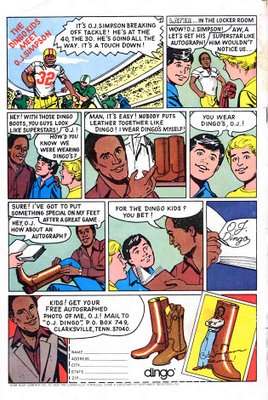

Violet Miranda: Girl Pirate #1-2

Published by Kiss Machine

Written by Emily Pohl-Weary

Illustrated by Willow Dawson

The Kiss Machine website describes this series as a graphic novel being released in four parts, with the creators having "envisioned Violet Miranda: Girl Pirate in response to the male-dominated comics industry's lack of positive role models for teen girls."

The comic is certainly distinctive-looking; Dawson's thick lines produce pages reminiscent of woodblock prints. The writer's choice of time period sets the book apart, too. Like El Cazador, CrossGen's short-lived series by Chuck Dixon and Steve Epting, Violet Miranda is a period piece, taking full advantage of the particularities of setting and characterization that the early eighteenth century affords. And as an adventure title centered upon two early modern female action heroines, this title is indeed refreshingly distinctive.

As in any good yarn, things are set in motion by some unexpected events. When the action begins, Violet Miranda and Elsa Bonnet are in their mid-teens, and have been living a sheltered existence on a small Caribbean island with their parents. It's clear that their paradisical existence is but a sojourn, since their fathers are on the run from someone or something, and live in fear that their hide-away will eventually be discovered.

The men's luck does indeed run out at the close of issue #1, and the island is invaded by a pirate named John, who is the son of the notorious Calico Jack Rackham. Violet and Elsa witness the murder of their fathers at the hands of the vengeance-driven marauder, and the girls and their mothers are taken captive.

John Rackham is written as an ambiguous character: he has killed the girls' fathers in cold blood, yet he forcefully enjoins his men not to molest the defenseless women. (It's no surprise that he is forced to back up the injunction with violence when one of the crew misbehaves.)

Additional ambiguity: we learn that the murdered men were not without blemish. While serving as crewmen under John's father they deserted (and possibly betrayed) him just before he was captured and consigned to the gallows. Prior to absconding, the two acquired a heap of treasure, and got hold of a map promising directions to untold riches. Since Calico Jack was engaged in the search for this self-same treasure prior to his capture, John believes its riches to be his birthright, and he intends to keep hold of the Violet, Elsa, and their mothers until he and his crew find it.

Issue #2 begins several months after the girls have been brought aboard John's ship, and we find that they've grown inured to life at sea. Though not at liberty, they're feeling and acting less like captives than they were at the close of the previous issue. One evening Violet asks John to explain the source of the feud between their fathers, and he complies, providing several capsule flashbacks depicting the colorful story of Calico Jack, and Mary Read and Anne Bonney, the two well-known female pirates.

I found Violet's lack of outward hostility towards the man who killed her father somewhat jarring. However, her stance is considerably tempered by an extended passage in which she recalls the dead man in flashback, with the final panel conveying to the reader that perhaps her public demeanor might not exactly match her inner emotions.

The core action in issue #2 concerns Violet and Elsa's training in sword-fighting; Violet cannily asks John to teach them how to defend themselves, in case the ship should fall into unwelcome hands. Having recently told detailed stories about his own mother's talents with both sword and pistol, John finds himself in no position to refuse the request.

After gaining considerable aptitude with wooden swords, John allows the girls to spar with true blades, and they soon surpass all of the men on board ship save the captain himself. The reader perceives (and indeed, hopes) that the girls might have their own motives, and a private conversation reveals some of their intentions.

Salty dogs, be warned: I would definitely watch out for Elsa.

Although issue #2 is more or less light-heartedly concerned with the girl's training in sword-fighting, there are several serious matters at the heart of things that just won't go away. After all, the story does concern four women being held against their will aboard a pirate ship. (Careful readers will note that Dawson always draws the older female characters with deeply lined and/or sunken eyes that betray their underlying concern over their condition.)

Towards the end of the issue, this is brought to the surface, as one of John's crewmen mentions that although they all recognize that Violet is his, Elsa's presence is inciting the men.

Issue #2 ends with a cliffhanger. The pirates are granted a two-week shore leave, and Elsa is trundled off to stay at the home of a crewman who happens to be a family man. (The other women join them.) Violet, however, is taken to parts unknown by John.

Several questions have been placed on the table:

— Why does John agree to train the girls?

— At one point he cryptically refers to them as his secret weapons; what does he mean?

— Is John a genuine rogue, or does he just work in an occupation that requires intermittent murderous behavior?

Violet Miranda: Girl Pirate joins Polly and the Pirates in ingeniously adding young women to this most durable and enjoyable of genres. I look forward to seeing how the ambiguities and details of this plot are resolved in future issues.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

Personal Archive, II

Who Are These People?

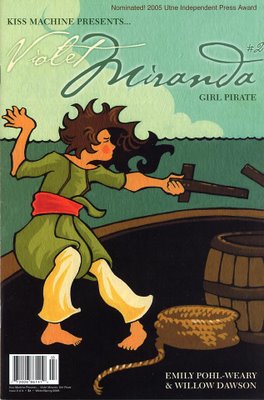

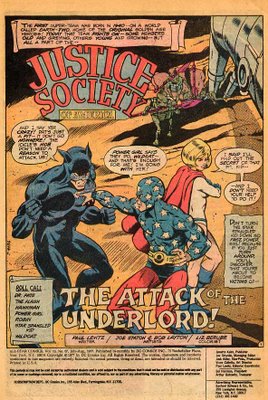

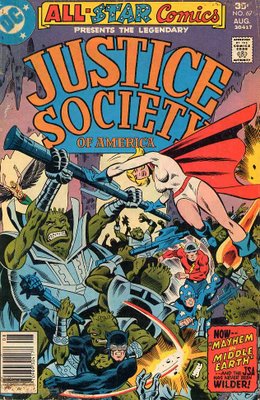

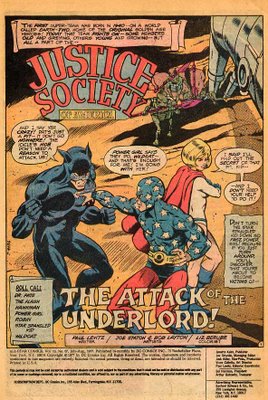

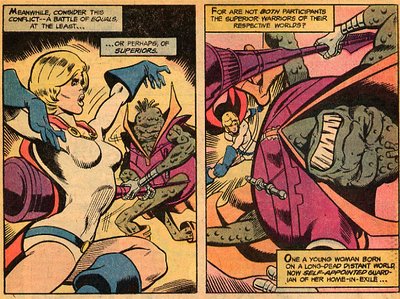

Justice Society of America #67 was a revelation for me; it was my first (and for a long time, only) exposure to Earth-Two. While the the captions and the characterizations made it easy enough for me to understand the setting and to get my bearings, it did take me some time to get used to the fact that Bruce Wayne was the Police Commissioner, and not wearing his mask and cape.

I especially liked that the generational distance between the old-timers and the youth was put to good use in the story. But what really grabbed me about this comic was that all of the action, and all of the people in it, moved in an orbit around the character of Power Girl. I wasn't aware of who she was before picking up this book, and when I finished it I felt cheated that no one had informed about her beforehand.

From the way she's drawn on the splash page, Power Girl's body language places her in opposition to her male teammates:

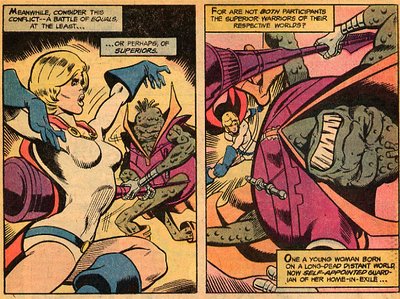

The book's plot is set into motion by her deduction that the key to unravelling the Injustice Society's sinister plan lies at the bottom of that nearby pit. And Power Girl does everything she can to ensure that the entire JSA ends up down there with her, even though they think she's screwey and doubt her line of reasoning. By the time the older members of the group do arrive, she's already thrown down with several bands of underground dwellers.

The book's plot is set into motion by her deduction that the key to unravelling the Injustice Society's sinister plan lies at the bottom of that nearby pit. And Power Girl does everything she can to ensure that the entire JSA ends up down there with her, even though they think she's screwey and doubt her line of reasoning. By the time the older members of the group do arrive, she's already thrown down with several bands of underground dwellers.

She proceeds to upbraid her colleagues for their tardiness, and even ends the encounter by proving that she didn't need their assistance after all.

Though it took my fourteen-year-old brain some time to integrate the information, I ultimately got it. A girl was the strongest member of the team: Power Girl was to the JSA as Superman was to the JLA.

The writer, Paul Levitz, underscored the point in these panels (through the deployment of some language that Stan Lee would have been proud to have penned).

Neither the fairly weak storyline, underdeveloped supporting characters, or the uninspiring villains detracted from my enjoyment of this comic book. I didn't quite understand where she had come from, and the present configuration of the JSA pretty much mystified me. But I knew that Power Girl was the genuine article.

As an infrequent reader of DC comics who was fourteen years old, that knowledge was all I needed.

Justice Society of America #67 was a revelation for me; it was my first (and for a long time, only) exposure to Earth-Two. While the the captions and the characterizations made it easy enough for me to understand the setting and to get my bearings, it did take me some time to get used to the fact that Bruce Wayne was the Police Commissioner, and not wearing his mask and cape.

I especially liked that the generational distance between the old-timers and the youth was put to good use in the story. But what really grabbed me about this comic was that all of the action, and all of the people in it, moved in an orbit around the character of Power Girl. I wasn't aware of who she was before picking up this book, and when I finished it I felt cheated that no one had informed about her beforehand.

From the way she's drawn on the splash page, Power Girl's body language places her in opposition to her male teammates:

The book's plot is set into motion by her deduction that the key to unravelling the Injustice Society's sinister plan lies at the bottom of that nearby pit. And Power Girl does everything she can to ensure that the entire JSA ends up down there with her, even though they think she's screwey and doubt her line of reasoning. By the time the older members of the group do arrive, she's already thrown down with several bands of underground dwellers.

The book's plot is set into motion by her deduction that the key to unravelling the Injustice Society's sinister plan lies at the bottom of that nearby pit. And Power Girl does everything she can to ensure that the entire JSA ends up down there with her, even though they think she's screwey and doubt her line of reasoning. By the time the older members of the group do arrive, she's already thrown down with several bands of underground dwellers. She proceeds to upbraid her colleagues for their tardiness, and even ends the encounter by proving that she didn't need their assistance after all.

Though it took my fourteen-year-old brain some time to integrate the information, I ultimately got it. A girl was the strongest member of the team: Power Girl was to the JSA as Superman was to the JLA.

The writer, Paul Levitz, underscored the point in these panels (through the deployment of some language that Stan Lee would have been proud to have penned).

Neither the fairly weak storyline, underdeveloped supporting characters, or the uninspiring villains detracted from my enjoyment of this comic book. I didn't quite understand where she had come from, and the present configuration of the JSA pretty much mystified me. But I knew that Power Girl was the genuine article.

As an infrequent reader of DC comics who was fourteen years old, that knowledge was all I needed.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

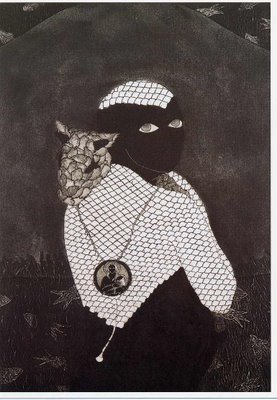

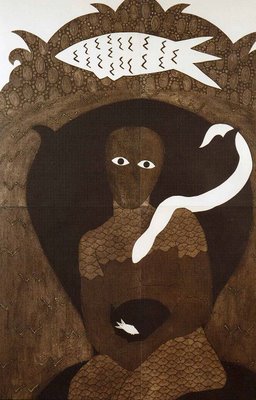

Belkis Ayón, 1967-1999

Untitled, (Sikán with a Goat), 1993

Belkis Ayón was a remarkable Cuban printmaker who spent a brief time at the end of her life producing art in the Philadelphia area. I became aware of her work in the fall of 2003, when I wandered into an exhibition of her large-scale collographic prints at the Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania.

A major inspiration for Ayón's works was the Afro-Cuban secret society of Abakúa, and central to Abakúa is the story of the fish-god Tánze and princess Sikán. These two paragraphs from Rosemary Branson Gill's essay in Belkis Ayón: Early Work (2003), explain how the two figures are linked:

Early one morning while Sikán was gathering water at the river, Tánze swam into her jug. The princess did not realize what had happened until she heard the sacred voice of Tánze speaking to her from the jug ... Believing that it was his voice and not his physical form that was holy, the male tribal elders took the fish and killed him in an attempt to preserve Tánze's voice in a drum. The drum, however, quickly fell silent. Since Sikán was the only human who had heard Tánze's voice, the elders considered her sacred and thus powerful enough to resurrect his voice. They sacrificed her, using her blood to bring back their god. Around this drum that beat out holy rhythms, the men formed the Secret Society of Abakúa.Here is how Ayón depicted Sikán in 1994:

Abukúa, while all male, only excludes women from contemporary participation; a force from the past, representative of femininity in general, is revered by the religion. In other words, although women cannot practice or be members, through Sikán there is a symbolic place for them in Abakúa. It was her blood, after all, that revived the voice of Tánze, and this miracle of resurrection is re-enacted today with goat's blood standing in for Sikán's own. The feminine becomes superhuman and a magical, if not divine, presence.

While I will grant you that Gill's second paragraph is both thought-provoking and contentious, what's not in question is that Ayón considered herself to be intimately connected to the traditions of this all-male worship group.

In 1996, Ayón produced a powerful untitled print (which others have subsequently called Sacrifice), which captures the horror, drama, and the sheer sense of cosmic necessity which are at the core of this primordial act.

In their "Introduction & Acknowledgments" to the exhibition catalogue, the curators mention that Ayón's "passing at the age of 32 represents a tear in the rich tapestry of contemporary Cuban art that has yet to be fully repaired or measured."

I'd only add that there are other artistic communities that keenly feel the sting of Ayón's absence, as well.

An Autonomous Character, II

She came, she saw, she kicked its ass.

A salutary image from Newsarama's preview of Birds of Prey #93. (Accessible here, with an additional four pages.)

Thank you, Gail Simone.

A salutary image from Newsarama's preview of Birds of Prey #93. (Accessible here, with an additional four pages.)

Thank you, Gail Simone.

Wednesday, April 12, 2006

Personal Archive, I

Wait, They Did What?

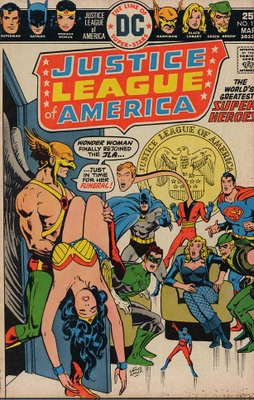

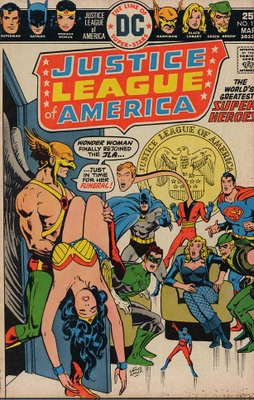

Though I wasn't a reader of DC comics when I was a boy, this cover certainly grabbed my attention. I knew who Wonder Woman was, of course, but had never read a comic book in which she played a major role. And, as I remember it, I hadn't yet discovered cynicism, because I actually paid for JLA #128 believing that I would soon learn of the circumstances surrounding Wonder Woman's demise.

The splash page sets things up in dramatic fashion:

However, careful observers will note that the Green Arrow isn't quite looking like himself, and neither is Batman. (In fact, they're both striking that Macauley Culkin pose from Home Alone.)

Before long we learn that Nekron's fear mojo has the rest of the JLA cowering for their lives to such an extent that they've all decided to quit.

So, following the "nothing is actually as it appears" rule, rather than a comic about Wonder Woman being cast out into the wilderness, she's pretty much the only character in the book who acts like a superhero.

As I said, I read this comic prior to my caring about being manipuated or jerked around. In fact, I followed the various twists and turns with interest, and I didn't feel cheated at all. I liked how Wonder Woman worked out what was really going on. And, even though the JLA rejected her, she turned it around, inspired them, and carried the team into battle during the showdown with the villain.

On another level, I was pleased to have consumed the book because it provided me with much-needed DC cred for those crucial out-of-school arguments about comics and superheroes. In future, whenever the discussion shifted to the DCU, I'd finally have something to contribute. Did you hear? Wonder Woman saved the entire JLA.

Man, I suppose that tells you how much I understood about schoolyard cred: Wonder Woman's actions got me absolutely nowhere in those testosterone-driven arguments about the coolness of particular superheroes. The Amazon princess was pretty much ignored by my circle of friends, until the Linda Carter TV show had its (ambiguous) impact and provided some measure of vindication.

Though I wasn't a reader of DC comics when I was a boy, this cover certainly grabbed my attention. I knew who Wonder Woman was, of course, but had never read a comic book in which she played a major role. And, as I remember it, I hadn't yet discovered cynicism, because I actually paid for JLA #128 believing that I would soon learn of the circumstances surrounding Wonder Woman's demise.

The splash page sets things up in dramatic fashion:

However, careful observers will note that the Green Arrow isn't quite looking like himself, and neither is Batman. (In fact, they're both striking that Macauley Culkin pose from Home Alone.)

Before long we learn that Nekron's fear mojo has the rest of the JLA cowering for their lives to such an extent that they've all decided to quit.

So, following the "nothing is actually as it appears" rule, rather than a comic about Wonder Woman being cast out into the wilderness, she's pretty much the only character in the book who acts like a superhero.

As I said, I read this comic prior to my caring about being manipuated or jerked around. In fact, I followed the various twists and turns with interest, and I didn't feel cheated at all. I liked how Wonder Woman worked out what was really going on. And, even though the JLA rejected her, she turned it around, inspired them, and carried the team into battle during the showdown with the villain.

On another level, I was pleased to have consumed the book because it provided me with much-needed DC cred for those crucial out-of-school arguments about comics and superheroes. In future, whenever the discussion shifted to the DCU, I'd finally have something to contribute. Did you hear? Wonder Woman saved the entire JLA.

Man, I suppose that tells you how much I understood about schoolyard cred: Wonder Woman's actions got me absolutely nowhere in those testosterone-driven arguments about the coolness of particular superheroes. The Amazon princess was pretty much ignored by my circle of friends, until the Linda Carter TV show had its (ambiguous) impact and provided some measure of vindication.

Monday, April 10, 2006

Dorothy Lathrop

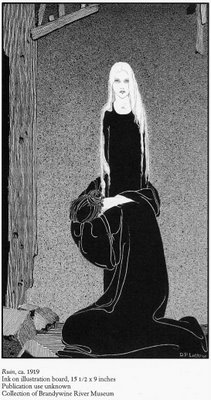

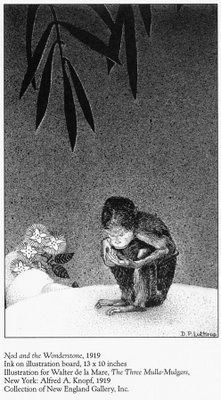

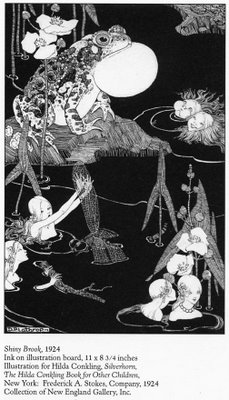

If you are interested in illustrations and prints, and are within travelling distance of Chadds Ford, PA, I urge you make a trip to the Brandywine River Museum to see "Flora, Fauna, and Fantasy: The Art of Dorothy Lathrop." (For those of you in the Albany, NY region, the exhibit will travel to the Albany Institute of History and Art, where it'll be from September 16 through the end of the year.)

There's been a lot of necessary (though soul-killing) paper-pushing going on under the glare of the flourescent lights here at Mortlake recently, so when friends offered an opportunity to leave the study and travel to the museum on a sunny Sunday morning, the offer was readily accepted.

Though the Brandywine River Museum is known for it's Wyeth collections, I was pleased beyond words to discover the collection of Dorothy Lathrop's prints, drawings, and illustrations.

Lathrop (1891-1980) was primarily a children's book illustrator; she won the first Caldecott award, and was also a winner of the Newberry Medal during her long and productive career. She was trained at Teacher's College in New York, at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, and the Arts League in NYC. As the illustration Ruin shows, she was a thorough-going modernist who was deeply influenced by Japanese print design.

Her first commission was to provide the illustrations for Walter de la Mare's The Three Mulla-Mulgars (1919), the story of three monkeys on a quest to find their royal uncle.

Lathrop's work on that book brought her wide attention and additional commissions; after 1931 she primarily illustrated her own stories.

While neither my sister nor I were raised on faerie stories, a particular variant of the genre was indeed prevalent during the historical period that I work on. Consequently, I've come to share a fascination for the genre's attention to themes of masking, impersonation, and hidden worlds with some of the figures whose lives I research.

Here's one of my favorite images from the show:

The exhibition catalogue provides a quote of Lathrap describing her methodology of passionate attention:

A person who does not love what he is drawing, whatever it may be, children or animals, or anything else, will not draw them convincingly, and that, simply because he will not bother to look at them long enough to really see them. What we love, we gloat over and feast our eyes upon. And when we look again and again at any living creature, we cannot help but perceive its subtlety of line, its exquisite patterning and all its intricacy and beauty. ... [O]ne who loves what he draws is very humbly trying to translate into alien medium life itself, and it is his joy and his pain that he knows that life to be matchless. (p. 7)

Sunday, April 09, 2006

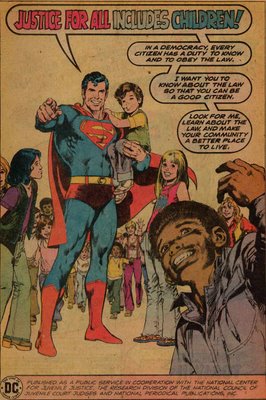

A Bicentennial Message

From my yellowing copy of the Justice League of America #128 (March 1976).

All I can say is, Superman should get into the habit of actually reading the ad copy before he gets to the recording studio.

In spite of my desire to make it so, his message is not a call for Americans to seek justice for children.

Instead, Superman is informing his readers that the social orderliness we all desire requires that even the nation's carefree youth must obey the laws and make their community a better place to live.

(And I always thought Superman was the one who frowned upon youth vigilantism.)

It might be argued that perhaps Superman is directing his comments more to his urban readers, here, imploring them to please, please, please stop trying to burn the motha' down.

Saturday, April 08, 2006

Many Wonder Women, V

The One Year Later edition.

This is Peter Kubert's variant cover to Wonder Woman #1, coming in June. (Via Newsarama; DC has posted an image of the "standard" cover, by Terry Dodson and Rachel Dodson, here.)

Is it possible that Hippolyta is alive on New Earth?

This is Peter Kubert's variant cover to Wonder Woman #1, coming in June. (Via Newsarama; DC has posted an image of the "standard" cover, by Terry Dodson and Rachel Dodson, here.)

Is it possible that Hippolyta is alive on New Earth?

Friday, April 07, 2006

No Girls Allowed?

In the April 2006 issue of Artforum magazine, Sarah Boxer provides a review of the recent "Masters of American Comics" exhibit at the UCLA Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angleles. (The full text of Boxer's review is accessible online, here.)

The review argues two points. The first is the problem of selection: why no women artists? Just to name one, the exclusion of Marjorie Henderson Buell, creator of Little Lulu, would seem to rank as a major oversight (or crime).

Boxer's second point deals with the masculinized fantasy world which creators built around their comic strip characters.

Rather than try to paraphrase her, here are two extended excerpts:

Boxer then proceeds to discuss R. Crumb's problematic portrayals of women.

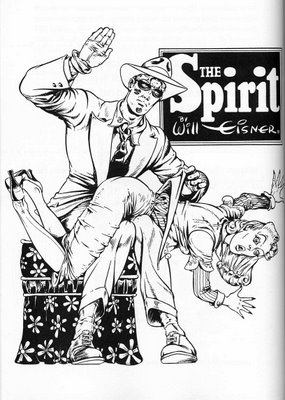

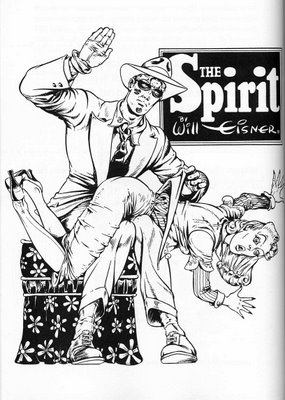

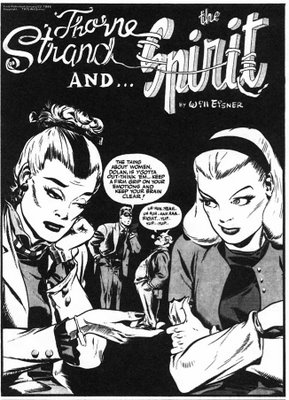

For the record, here's a black and white image of the Eisner drawing that takes on special meaning for Boxer in the context of the exhibit she viewed. (It's a scan from Eisner/Miller, [Dark Horse Books, 2005], p. 66.)

No doubt about it, that'd be the last Eisner image I'd consider including in an exhibition that entirely excluded female creators. Boxer indeed makes a necessary point about context.

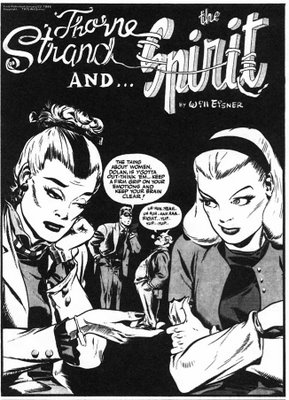

However, in a previous post I commented upon Eisner's propensity for creating interesting, strong female characters. (At The Written World, Ragnell posted on a notable one, Satin.) And in his own defense, this is the illustration that follows Ms. Dolan's spanking in Eisner/Miller:

Boxer's review essay is well worth reading in it's entirety. It's interesting how a museum exhibit can create its own little enclosed world, where new perspectives and points of view can be revealed. (For example, I hadn't thought about the de-feminized world of Gasoline Alley until I read this review.) As Boxer shows, examining the works selected to comprise an exhibit's small visual universe can also prove revelatory.

The review argues two points. The first is the problem of selection: why no women artists? Just to name one, the exclusion of Marjorie Henderson Buell, creator of Little Lulu, would seem to rank as a major oversight (or crime).

Boxer's second point deals with the masculinized fantasy world which creators built around their comic strip characters.

Rather than try to paraphrase her, here are two extended excerpts:

The exhibition has plenty of room for Little Annie Fanny, Kurtzman's long-running Playboy strip, but none for empty-eyed Little Orphan Annie. And though there's a place for two parodies (one by Spiegelman, the other by Panter) of Ernie Bushmiller's annoying, spike-haired child Nancy, the real Nancy is missing. Isn't this just like showing Warhol's Dick Tracy without Gould's original? And where is Lynda Barry, Roz Chast, Mary Fleener, or any female artist?

Oh, but there are women. They're on the walls, as a perpetual underclass. Every high must have its low, and the unspoken mastery in "Masters of American Comics" is, it turns out, over women. The misogyny in comics is no big secret, but rather than reflect on it, the curators have simply picked comics entirely by and mostly about males. As a result, viewers may find themselves wondering whether there is something about the very will to fantasize and draw comics that is bound up with antipathy toward women.

Let's follow the trail all the way back to Little Nemo, the earliest comic in the show. On January 26, 1908, Little Nemo wakes from a fantastical dream in which he can't find his way out of the maze of mirrors in Befuddle Hall. "Nemo! Are you up! Do you want me to spank you? Go to sleep!" says his mother. Another dream ends with Nemo asking, "Aw Ma-ma! Why did you wake me up?" She answers: "Because you are kicking the covers off. You do it again and I'll spank you, do you understand?" The boy stares out at us, astonished.

That pretty much sums up the predominant attitude (explicit or not) of comics toward women. They're the creatures that shake you out of fantasy land. No wonder they're not allowed in the clubhouse.

...

OK, so there aren't many female action heroes to choose from, but what about domestic comic strips? The curators chose Gasoline Alley, a strip that is graphically ingenious, true enough, but also creepily devoid of women. The tender bond between Walt and his foundling son, Skeezix, leaves no room for them: The two guys explore worlds of fantasy, nature, cars, and color all by themselves.

In the second half of the exhibition, where the focus is on postwar artists, from Eisner to Ware, the antipathy toward women comes to the fore. A large drawing for The Spirit, Eisner's comic about a masked hero with no superpowers, drives the point home: The Spirit, lipstick smeared on his cheek, bends the culprit kisser over his knee and spanks her. Take that! It was the only spanking the Spirit ever delivered, and the drawing became a cult favorite. But in this show, it stands out as a reversal of fortunes, sweet revenge for Little Nemo's threatened spanking. And, boy, did revenge ever come.

Boxer then proceeds to discuss R. Crumb's problematic portrayals of women.

For the record, here's a black and white image of the Eisner drawing that takes on special meaning for Boxer in the context of the exhibit she viewed. (It's a scan from Eisner/Miller, [Dark Horse Books, 2005], p. 66.)

No doubt about it, that'd be the last Eisner image I'd consider including in an exhibition that entirely excluded female creators. Boxer indeed makes a necessary point about context.

However, in a previous post I commented upon Eisner's propensity for creating interesting, strong female characters. (At The Written World, Ragnell posted on a notable one, Satin.) And in his own defense, this is the illustration that follows Ms. Dolan's spanking in Eisner/Miller:

Boxer's review essay is well worth reading in it's entirety. It's interesting how a museum exhibit can create its own little enclosed world, where new perspectives and points of view can be revealed. (For example, I hadn't thought about the de-feminized world of Gasoline Alley until I read this review.) As Boxer shows, examining the works selected to comprise an exhibit's small visual universe can also prove revelatory.

Thursday, April 06, 2006

I Buy Things

I splurged, and purchased the Sadie and Katie doll from the Camille Rose Garcia series that's been produced by the Necessaries Toy Foundation.

Garcia's painting "Pitco Production Plant," from her Operation Opticon series, depicts the conjoined twins. (The image is from Camille Rose Garcia's website.)

Here's a picture of the doll, taken at Mortlake:

I'm pleased to report that I am not alone.

Garcia's painting "Pitco Production Plant," from her Operation Opticon series, depicts the conjoined twins. (The image is from Camille Rose Garcia's website.)

Here's a picture of the doll, taken at Mortlake:

I'm pleased to report that I am not alone.

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

Links

Ragnell has compiled The Carnival of the Feminists XII over at The Written World. (I'm honored to have a post of mine listed there.)

Hatshepsut, Pharaoh of Egypt from 1503 B.C.E. to 1482 B.C.E., is described in a compelling Newsweek International article, which announces this exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. (The wikipedia entry on Hatshepsut makes for fascinating reading, too.)

A brief, objective listing of facts: Boston, World Series Champions 2004; Chicago White Sox, in 2005; insect-guided munitions will soon be in production; and now, Windows running on Apple machines! And you require additional signs of an impending apocalypse?

On Monday, Ragnell posted "Fan-What?" at The Written World, in which she examined the term fan- boy/girl. The post and the comments are well worth consulting, and they taught me something about the categorization of some of my own interests and tastes in comics.

Well, I'm off to confront the rest of an adventure-stuffed day, one of which will be my eager purchase of a copy of Spider-Girl #97.

So, this is Melchior del Darién signing off for now, proud to say that I've been fangirling online here since October 2005.

Hatshepsut, Pharaoh of Egypt from 1503 B.C.E. to 1482 B.C.E., is described in a compelling Newsweek International article, which announces this exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. (The wikipedia entry on Hatshepsut makes for fascinating reading, too.)

A brief, objective listing of facts: Boston, World Series Champions 2004; Chicago White Sox, in 2005; insect-guided munitions will soon be in production; and now, Windows running on Apple machines! And you require additional signs of an impending apocalypse?

On Monday, Ragnell posted "Fan-What?" at The Written World, in which she examined the term fan- boy/girl. The post and the comments are well worth consulting, and they taught me something about the categorization of some of my own interests and tastes in comics.

Well, I'm off to confront the rest of an adventure-stuffed day, one of which will be my eager purchase of a copy of Spider-Girl #97.

So, this is Melchior del Darién signing off for now, proud to say that I've been fangirling online here since October 2005.

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

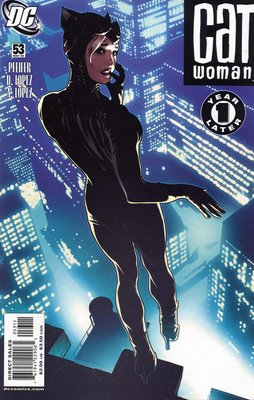

Selina Kyle OYL

Spoilers to Catwoman #53 follow.

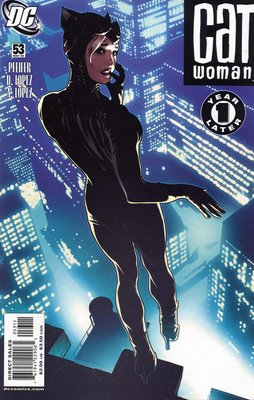

The important facts that are introduced in this issue have been bandied about the Internet for several months: Selina Kyle is a mom, and she's no longer Catwoman. Holly Robinson, her friend and protegé, has just taken up the mantle. And, with someone younger and less experienced occupying the role, readers are shown that being Catwoman is no simple task.

It's clear that Will Pfeifer intends to ease our transition into Selina Kyle's corner of the DCU, and those readers desiring quick answers are going to be disappointed. In a fundamental way, Catwoman one year later is all about uncertainty, and the cover image I've reproduced, (which is different from the picture up at DC's website), shows us the newly-costumed heroine with her hand up to her face, the finger in her mouth connoting hesitation and insecurity.

These were the questions I brought to this issue:

Will Selina Kyle be both mother and heroine?

Why does Selina think she can so easily be replaced?

Can Holly Robinson stay alive as the new Catwoman (without killing someone)?

Where has baby Helena come from, and what's her destiny?

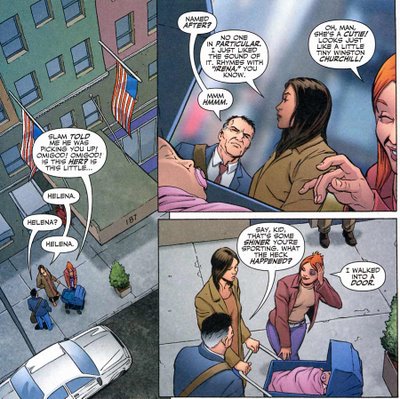

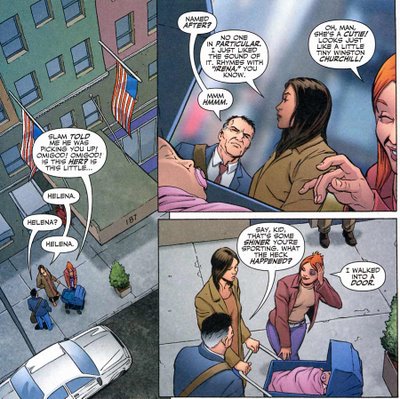

I know that the last question is oddly-worded, but there's more to this, I think, than simply finding out who Helena's father is. For example, there's an interesting exchange between Slam Bradley and Selina over her choice of the child's name.

Slam's reaction here intrigues me because, other than for considerations that exist beyond the fourth wall, I don't quite get why the name Helena should cause him to raise an eyebrow. I mean, the name should evoke all kinds of connections for the reader, but not for the characters in the book, right?

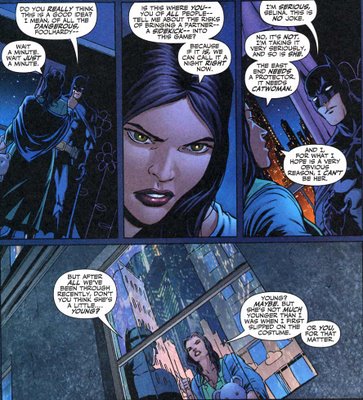

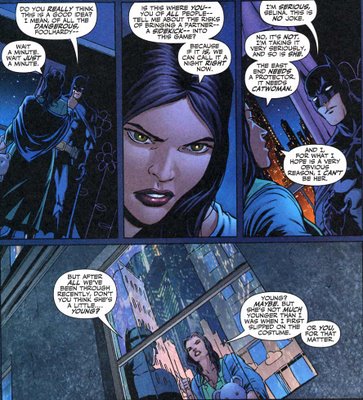

It's heartening to see that even after the crisis and the leap forward, Selina is still herself. Let me set the stage for her last appearance in the issue. Batman has stopped by to visit and chat. Selina has recently given birth, (having been released from the hospital with her child several hours earlier). She's got a motherly shawl draped over her shoulders, and looks as if she's gearing up for an evening of knitting in front of the radio (or Victrola). She lacks all of the outer accoutrements of mask and costume that mark her as an accomplished adventuress. Oh, and there's one last thing: she's holding a teddy bear in one hand.

Yet, when Batman begins his lecture on the wisdom of her decision to empower Holly Robinson as the new Catwoman, Selina cuts him off and firmly directs Batman to talk to the hand.

One year later, Selina Kyle is absolutely at peace with the momentous decisions she has made. I look forward to learning about the sources of her confidence in future issues.

The important facts that are introduced in this issue have been bandied about the Internet for several months: Selina Kyle is a mom, and she's no longer Catwoman. Holly Robinson, her friend and protegé, has just taken up the mantle. And, with someone younger and less experienced occupying the role, readers are shown that being Catwoman is no simple task.

It's clear that Will Pfeifer intends to ease our transition into Selina Kyle's corner of the DCU, and those readers desiring quick answers are going to be disappointed. In a fundamental way, Catwoman one year later is all about uncertainty, and the cover image I've reproduced, (which is different from the picture up at DC's website), shows us the newly-costumed heroine with her hand up to her face, the finger in her mouth connoting hesitation and insecurity.

These were the questions I brought to this issue:

Will Selina Kyle be both mother and heroine?

Why does Selina think she can so easily be replaced?

Can Holly Robinson stay alive as the new Catwoman (without killing someone)?

Where has baby Helena come from, and what's her destiny?

I know that the last question is oddly-worded, but there's more to this, I think, than simply finding out who Helena's father is. For example, there's an interesting exchange between Slam Bradley and Selina over her choice of the child's name.

Slam's reaction here intrigues me because, other than for considerations that exist beyond the fourth wall, I don't quite get why the name Helena should cause him to raise an eyebrow. I mean, the name should evoke all kinds of connections for the reader, but not for the characters in the book, right?

It's heartening to see that even after the crisis and the leap forward, Selina is still herself. Let me set the stage for her last appearance in the issue. Batman has stopped by to visit and chat. Selina has recently given birth, (having been released from the hospital with her child several hours earlier). She's got a motherly shawl draped over her shoulders, and looks as if she's gearing up for an evening of knitting in front of the radio (or Victrola). She lacks all of the outer accoutrements of mask and costume that mark her as an accomplished adventuress. Oh, and there's one last thing: she's holding a teddy bear in one hand.

Yet, when Batman begins his lecture on the wisdom of her decision to empower Holly Robinson as the new Catwoman, Selina cuts him off and firmly directs Batman to talk to the hand.

One year later, Selina Kyle is absolutely at peace with the momentous decisions she has made. I look forward to learning about the sources of her confidence in future issues.

Monday, April 03, 2006

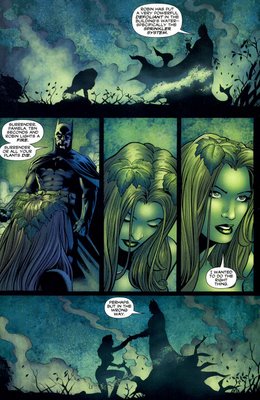

You Don't Bring Me Flowers...

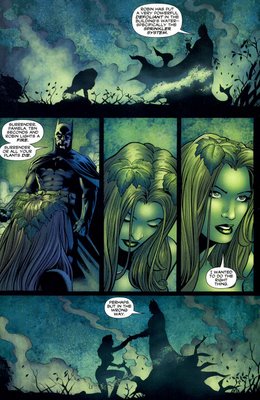

This post contains spoilers to Batman #651.

In the previous issue we were shown that Poison Ivy was wielding enhanced power; her plants were swarming all over the top tier of a major skyscraper. So it struck me that the writer missed an opportunity in this issue, since Ivy is outsmarted, overcome, and escorted to Arkham Asylum fairly effortlessly, (in a manner that I thought was reminiscent of the 60s television show).

I was intrigued by the artist's choice of imagery in depicting her "Oh, I give up" moment:

Does this look to anyone else as if it's the climactic moment in a fairy tale? If that's what this is supposed to evoke, shouldn't the knight be on his knees, anyway?

Did I miss something, or has Ivy just asked Batman to marry her?

In the previous issue we were shown that Poison Ivy was wielding enhanced power; her plants were swarming all over the top tier of a major skyscraper. So it struck me that the writer missed an opportunity in this issue, since Ivy is outsmarted, overcome, and escorted to Arkham Asylum fairly effortlessly, (in a manner that I thought was reminiscent of the 60s television show).

I was intrigued by the artist's choice of imagery in depicting her "Oh, I give up" moment:

Does this look to anyone else as if it's the climactic moment in a fairy tale? If that's what this is supposed to evoke, shouldn't the knight be on his knees, anyway?

Did I miss something, or has Ivy just asked Batman to marry her?

Saturday, April 01, 2006

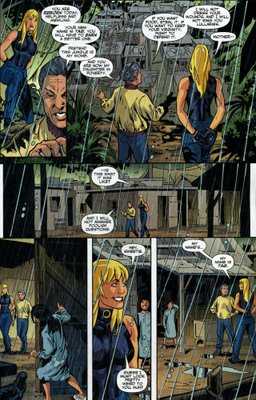

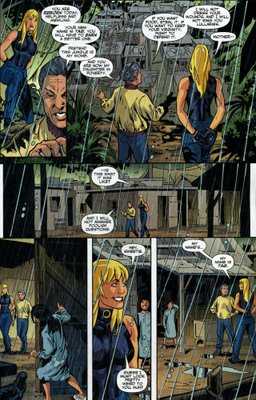

An Autonomous Character OYL

Birds of Prey #92 spoilers follow.

Prior to the actual release of Birds of Prey #92, a reader who had seen an advance copy spilled the beans over at the DC Message Boards. However, when the poster wrote that Dinah was being held captive somewhere in Asia, I immediately doubted this, since Gail Simone has made clear that Dinah's recent campaign to better her martial arts skills has partially been driven by a desire never to be anyone's hostage again. (And, one presumes, Simone should know better than anyone what Dinah's thoughts are, and what situations she might face.)

It turns out the poster was indeed very wrong; Dinah is not being held captive. Instead, Simone has cleverly established a compelling plot-element which only continued reading can explain: how has the pursuit of kung-fu mojo brought Dinah to willingly relinquish the personal autonomy she values so highly?

We learn that Dinah intends to subject herself to some very harsh training; at the start of her first "exercise," a bag is secured over her head and she's attacked without restraint by a group of club wielding men. Although that "fight," (portions of which are threaded through the last part of the comic), was difficult for me to read, this page made an equally strong impression on me.

If we had any lingering doubts that Dinah's journey is voluntary, Simone skillfully shows us the moments at which the character openly gives voice to her complicity in her own powerlessness. First, Dinah calls the older woman "Mother." Later, she corrects herself, telling the girl that her name is Tag.

In Black Canary's case, Gail Simone has made excellent use of the jump to "One Year Later." The character has been placed in the midst of a compelling new situation, and the reader awaits answers and further developments. In addition, there's a lot more going on in the book: I haven't even revealed several other big surprises Simone provides in this issue.

Birds of Prey remains one of my favorite DC titles.

Prior to the actual release of Birds of Prey #92, a reader who had seen an advance copy spilled the beans over at the DC Message Boards. However, when the poster wrote that Dinah was being held captive somewhere in Asia, I immediately doubted this, since Gail Simone has made clear that Dinah's recent campaign to better her martial arts skills has partially been driven by a desire never to be anyone's hostage again. (And, one presumes, Simone should know better than anyone what Dinah's thoughts are, and what situations she might face.)

It turns out the poster was indeed very wrong; Dinah is not being held captive. Instead, Simone has cleverly established a compelling plot-element which only continued reading can explain: how has the pursuit of kung-fu mojo brought Dinah to willingly relinquish the personal autonomy she values so highly?

We learn that Dinah intends to subject herself to some very harsh training; at the start of her first "exercise," a bag is secured over her head and she's attacked without restraint by a group of club wielding men. Although that "fight," (portions of which are threaded through the last part of the comic), was difficult for me to read, this page made an equally strong impression on me.

If we had any lingering doubts that Dinah's journey is voluntary, Simone skillfully shows us the moments at which the character openly gives voice to her complicity in her own powerlessness. First, Dinah calls the older woman "Mother." Later, she corrects herself, telling the girl that her name is Tag.

In Black Canary's case, Gail Simone has made excellent use of the jump to "One Year Later." The character has been placed in the midst of a compelling new situation, and the reader awaits answers and further developments. In addition, there's a lot more going on in the book: I haven't even revealed several other big surprises Simone provides in this issue.

Birds of Prey remains one of my favorite DC titles.