Thursday, April 13, 2006

Belkis Ayón, 1967-1999

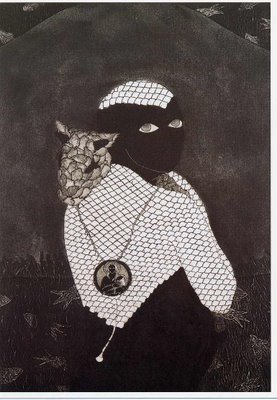

Untitled, (Sikán with a Goat), 1993

Belkis Ayón was a remarkable Cuban printmaker who spent a brief time at the end of her life producing art in the Philadelphia area. I became aware of her work in the fall of 2003, when I wandered into an exhibition of her large-scale collographic prints at the Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania.

A major inspiration for Ayón's works was the Afro-Cuban secret society of Abakúa, and central to Abakúa is the story of the fish-god Tánze and princess Sikán. These two paragraphs from Rosemary Branson Gill's essay in Belkis Ayón: Early Work (2003), explain how the two figures are linked:

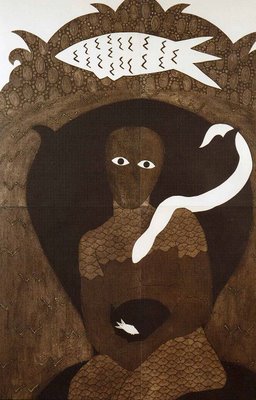

Early one morning while Sikán was gathering water at the river, Tánze swam into her jug. The princess did not realize what had happened until she heard the sacred voice of Tánze speaking to her from the jug ... Believing that it was his voice and not his physical form that was holy, the male tribal elders took the fish and killed him in an attempt to preserve Tánze's voice in a drum. The drum, however, quickly fell silent. Since Sikán was the only human who had heard Tánze's voice, the elders considered her sacred and thus powerful enough to resurrect his voice. They sacrificed her, using her blood to bring back their god. Around this drum that beat out holy rhythms, the men formed the Secret Society of Abakúa.Here is how Ayón depicted Sikán in 1994:

Abukúa, while all male, only excludes women from contemporary participation; a force from the past, representative of femininity in general, is revered by the religion. In other words, although women cannot practice or be members, through Sikán there is a symbolic place for them in Abakúa. It was her blood, after all, that revived the voice of Tánze, and this miracle of resurrection is re-enacted today with goat's blood standing in for Sikán's own. The feminine becomes superhuman and a magical, if not divine, presence.

While I will grant you that Gill's second paragraph is both thought-provoking and contentious, what's not in question is that Ayón considered herself to be intimately connected to the traditions of this all-male worship group.

In 1996, Ayón produced a powerful untitled print (which others have subsequently called Sacrifice), which captures the horror, drama, and the sheer sense of cosmic necessity which are at the core of this primordial act.

In their "Introduction & Acknowledgments" to the exhibition catalogue, the curators mention that Ayón's "passing at the age of 32 represents a tear in the rich tapestry of contemporary Cuban art that has yet to be fully repaired or measured."

I'd only add that there are other artistic communities that keenly feel the sting of Ayón's absence, as well.