Friday, April 07, 2006

No Girls Allowed?

In the April 2006 issue of Artforum magazine, Sarah Boxer provides a review of the recent "Masters of American Comics" exhibit at the UCLA Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angleles. (The full text of Boxer's review is accessible online, here.)

The review argues two points. The first is the problem of selection: why no women artists? Just to name one, the exclusion of Marjorie Henderson Buell, creator of Little Lulu, would seem to rank as a major oversight (or crime).

Boxer's second point deals with the masculinized fantasy world which creators built around their comic strip characters.

Rather than try to paraphrase her, here are two extended excerpts:

Boxer then proceeds to discuss R. Crumb's problematic portrayals of women.

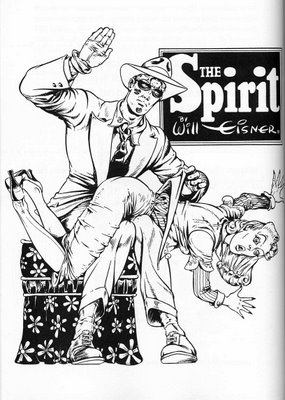

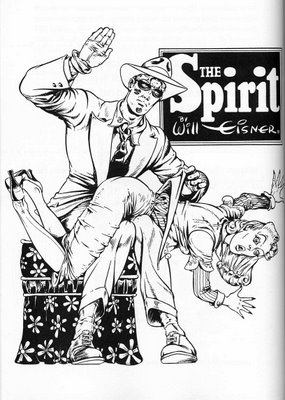

For the record, here's a black and white image of the Eisner drawing that takes on special meaning for Boxer in the context of the exhibit she viewed. (It's a scan from Eisner/Miller, [Dark Horse Books, 2005], p. 66.)

No doubt about it, that'd be the last Eisner image I'd consider including in an exhibition that entirely excluded female creators. Boxer indeed makes a necessary point about context.

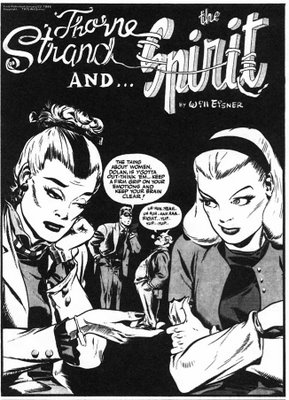

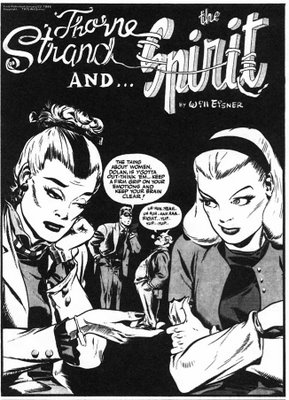

However, in a previous post I commented upon Eisner's propensity for creating interesting, strong female characters. (At The Written World, Ragnell posted on a notable one, Satin.) And in his own defense, this is the illustration that follows Ms. Dolan's spanking in Eisner/Miller:

Boxer's review essay is well worth reading in it's entirety. It's interesting how a museum exhibit can create its own little enclosed world, where new perspectives and points of view can be revealed. (For example, I hadn't thought about the de-feminized world of Gasoline Alley until I read this review.) As Boxer shows, examining the works selected to comprise an exhibit's small visual universe can also prove revelatory.

The review argues two points. The first is the problem of selection: why no women artists? Just to name one, the exclusion of Marjorie Henderson Buell, creator of Little Lulu, would seem to rank as a major oversight (or crime).

Boxer's second point deals with the masculinized fantasy world which creators built around their comic strip characters.

Rather than try to paraphrase her, here are two extended excerpts:

The exhibition has plenty of room for Little Annie Fanny, Kurtzman's long-running Playboy strip, but none for empty-eyed Little Orphan Annie. And though there's a place for two parodies (one by Spiegelman, the other by Panter) of Ernie Bushmiller's annoying, spike-haired child Nancy, the real Nancy is missing. Isn't this just like showing Warhol's Dick Tracy without Gould's original? And where is Lynda Barry, Roz Chast, Mary Fleener, or any female artist?

Oh, but there are women. They're on the walls, as a perpetual underclass. Every high must have its low, and the unspoken mastery in "Masters of American Comics" is, it turns out, over women. The misogyny in comics is no big secret, but rather than reflect on it, the curators have simply picked comics entirely by and mostly about males. As a result, viewers may find themselves wondering whether there is something about the very will to fantasize and draw comics that is bound up with antipathy toward women.

Let's follow the trail all the way back to Little Nemo, the earliest comic in the show. On January 26, 1908, Little Nemo wakes from a fantastical dream in which he can't find his way out of the maze of mirrors in Befuddle Hall. "Nemo! Are you up! Do you want me to spank you? Go to sleep!" says his mother. Another dream ends with Nemo asking, "Aw Ma-ma! Why did you wake me up?" She answers: "Because you are kicking the covers off. You do it again and I'll spank you, do you understand?" The boy stares out at us, astonished.

That pretty much sums up the predominant attitude (explicit or not) of comics toward women. They're the creatures that shake you out of fantasy land. No wonder they're not allowed in the clubhouse.

...

OK, so there aren't many female action heroes to choose from, but what about domestic comic strips? The curators chose Gasoline Alley, a strip that is graphically ingenious, true enough, but also creepily devoid of women. The tender bond between Walt and his foundling son, Skeezix, leaves no room for them: The two guys explore worlds of fantasy, nature, cars, and color all by themselves.

In the second half of the exhibition, where the focus is on postwar artists, from Eisner to Ware, the antipathy toward women comes to the fore. A large drawing for The Spirit, Eisner's comic about a masked hero with no superpowers, drives the point home: The Spirit, lipstick smeared on his cheek, bends the culprit kisser over his knee and spanks her. Take that! It was the only spanking the Spirit ever delivered, and the drawing became a cult favorite. But in this show, it stands out as a reversal of fortunes, sweet revenge for Little Nemo's threatened spanking. And, boy, did revenge ever come.

Boxer then proceeds to discuss R. Crumb's problematic portrayals of women.

For the record, here's a black and white image of the Eisner drawing that takes on special meaning for Boxer in the context of the exhibit she viewed. (It's a scan from Eisner/Miller, [Dark Horse Books, 2005], p. 66.)

No doubt about it, that'd be the last Eisner image I'd consider including in an exhibition that entirely excluded female creators. Boxer indeed makes a necessary point about context.

However, in a previous post I commented upon Eisner's propensity for creating interesting, strong female characters. (At The Written World, Ragnell posted on a notable one, Satin.) And in his own defense, this is the illustration that follows Ms. Dolan's spanking in Eisner/Miller:

Boxer's review essay is well worth reading in it's entirety. It's interesting how a museum exhibit can create its own little enclosed world, where new perspectives and points of view can be revealed. (For example, I hadn't thought about the de-feminized world of Gasoline Alley until I read this review.) As Boxer shows, examining the works selected to comprise an exhibit's small visual universe can also prove revelatory.