Thursday, March 30, 2006

Male Noir Heroes

As I said in my post about X-Factor #5, the central male figures in noir films often had to overcome significant submissive experiences before they ultimately went on to "reclaim" their heroic and, (in the preferred coding of the time period), masculine status.

To illustrate what I've been getting at, here's a still from Howard Hawks' The Big Sleep (1946):

A brief description:

Essential reading:

E. Ann Kaplan, (ed.), Women in Film Noir, (British Film Institute, 2d ed, 1980).

D. Thomson, The Big Sleep, (BFI, 1997).

M. Eaton, Chinatown, (BFI, 1997).

P. Shrader, "Notes on Noir," in Grant, (ed.), Film Genre Reader II, (Texas, 1995).

To illustrate what I've been getting at, here's a still from Howard Hawks' The Big Sleep (1946):

A brief description:

[T]here is a sadistic aplomb in the way Canino lets ball bearings spill from his hand just after he has slugged Marlowe [Bogart]. Then Marlowe comes to, and he's tied up and handcuffed, with an open wound in his jaw. Mrs Eddie Mars is there ... Marlowe rides her, taunts her ... until she tosses liquor in his open wound. And then Marlowe is left with Vivian [Bacall]. ... Of course, she unties him, with another kiss first, the more sensual because he is tied up... (Thomson, pp. 47 & 49)

Essential reading:

E. Ann Kaplan, (ed.), Women in Film Noir, (British Film Institute, 2d ed, 1980).

D. Thomson, The Big Sleep, (BFI, 1997).

M. Eaton, Chinatown, (BFI, 1997).

P. Shrader, "Notes on Noir," in Grant, (ed.), Film Genre Reader II, (Texas, 1995).

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

For Home or Office

From the Archie McPhee catalogue, Collector's Edition #72

The oddly appealing Avenging Unicorn Play Set.

Chuck Norris says: if you see the Avenging Unicorn, then you are already dead.

The oddly appealing Avenging Unicorn Play Set.

Chuck Norris says: if you see the Avenging Unicorn, then you are already dead.

Monday, March 27, 2006

Quien es Macho? Siryn es Macho!

This post contains major spoilers to X-Factor #5.

When I said in my earlier post that there was a lot was going on in X-Factor #5, what I really meant was that my reactions to the issue have been all over the place.

Because what actually happens in the comic is that Siryn (who, just to fill you in, was beaten to within an inch of her life at the close of the previous issue) is held captive in a theater by Dr. Leery, a former mutant who is mightily pissed off over the loss of his powers. (Leery stumbled upon the heroine as she lay unconscious; her attacker had left her for dead.) It's the villain's belief that those mutants such as Siryn who have retained their powers after "The Decimation" are secretly in league with whoever is responsible for the event.

The good news: the villain has treated several of Siryn's more severe wounds. The bad: he intends to mutilate his captive in order to send body-part messages to her buddies at X-Factor Investigations. Adding to the suspense is the fact that the investigator following Siryn's trail is Rictor, the firm's sole de-powered member.

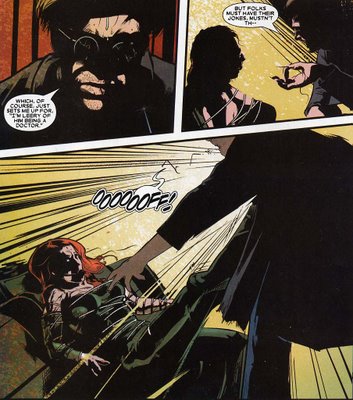

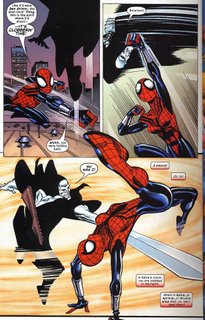

I have to admit that the comic was hard to read in places. In addition to the images that I previously posted, there are also quite a few unpleasant panels like these:

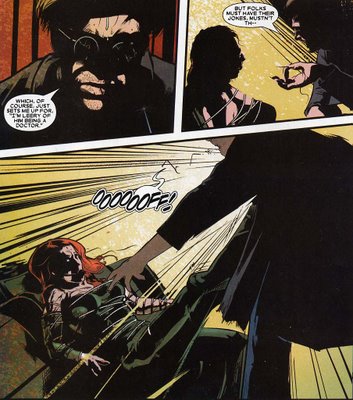

Standard damsel-in-distress imagery, right? Clearly we're going to have to bide our time and patiently await the arrival of a more competent male hero to save the day. But just when my angry brain began to think this, the creators provided more salutary imagery, like this:

(I should add that Leery re-set several of his captive's broken bones, one of which was her right leg. Poetic justice!)

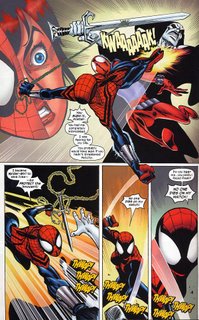

Although she spends most of the issue under someone else's power, the creators do work to redeem Siryn as a viable modern superheroine. Even after Rictor arrives on the scene, she gathers her strength and makes a major contribution to the take-down of the villain:

While it's clear that Peter A. David wants to subvert the sexist trope of the woman who needs a man to deliver her from a dangerous situation, does he succeed?

My answer: yes, just barely. (And I'd have major reservations if this storyline were dragged out into another issue.) Here's my thinking:

I understand that this is a comic book, and that a title gets boring fast if the heroine is constantly kicking people's asses, and never can get her own ass kicked by anyone. I also get that X-Factor is giving off a noirish vibe. Bogart, Robert Mitchum, and Alan Ladd were constantly getting their asses handed to them by minor gunsels and cretinous henchmen in the middle reels of their respective noir movies. And, although the "message" of noir is that the hero can never destroy the interconnected webs of corruption in which he's ensnared, the viewer is at the very least assured that by the final reel the hero will have administered compensatory beat-downs to any of the players who were stupid enough to have laid a hand on him. The comic works then, and doesn't offend, if we accept that Siryn is a noirish or Bogart-ian heroine. Final confirmation of this line of interpretation will come if David actually shows us how Siryn finds and "re-pays" her original assailant in future issues.

Rather than a weak-damsel story, Peter David wants us to read X-Factor #5 as if it were an episode in the comic-book version of the Saturday Night Live gameshow Quien Es Mas Macho? (Who is More Macho?) And I'm pleased to report that, in the match-up of Siryn vs. Dr. Leery, Siryn es mas macho. She proves herself to be, indeed, muy muy macho.

And, by his own admission, Siryn's got Rictor beat, too.

When I said in my earlier post that there was a lot was going on in X-Factor #5, what I really meant was that my reactions to the issue have been all over the place.

Because what actually happens in the comic is that Siryn (who, just to fill you in, was beaten to within an inch of her life at the close of the previous issue) is held captive in a theater by Dr. Leery, a former mutant who is mightily pissed off over the loss of his powers. (Leery stumbled upon the heroine as she lay unconscious; her attacker had left her for dead.) It's the villain's belief that those mutants such as Siryn who have retained their powers after "The Decimation" are secretly in league with whoever is responsible for the event.

The good news: the villain has treated several of Siryn's more severe wounds. The bad: he intends to mutilate his captive in order to send body-part messages to her buddies at X-Factor Investigations. Adding to the suspense is the fact that the investigator following Siryn's trail is Rictor, the firm's sole de-powered member.

I have to admit that the comic was hard to read in places. In addition to the images that I previously posted, there are also quite a few unpleasant panels like these:

Standard damsel-in-distress imagery, right? Clearly we're going to have to bide our time and patiently await the arrival of a more competent male hero to save the day. But just when my angry brain began to think this, the creators provided more salutary imagery, like this:

(I should add that Leery re-set several of his captive's broken bones, one of which was her right leg. Poetic justice!)

Although she spends most of the issue under someone else's power, the creators do work to redeem Siryn as a viable modern superheroine. Even after Rictor arrives on the scene, she gathers her strength and makes a major contribution to the take-down of the villain:

While it's clear that Peter A. David wants to subvert the sexist trope of the woman who needs a man to deliver her from a dangerous situation, does he succeed?

My answer: yes, just barely. (And I'd have major reservations if this storyline were dragged out into another issue.) Here's my thinking:

I understand that this is a comic book, and that a title gets boring fast if the heroine is constantly kicking people's asses, and never can get her own ass kicked by anyone. I also get that X-Factor is giving off a noirish vibe. Bogart, Robert Mitchum, and Alan Ladd were constantly getting their asses handed to them by minor gunsels and cretinous henchmen in the middle reels of their respective noir movies. And, although the "message" of noir is that the hero can never destroy the interconnected webs of corruption in which he's ensnared, the viewer is at the very least assured that by the final reel the hero will have administered compensatory beat-downs to any of the players who were stupid enough to have laid a hand on him. The comic works then, and doesn't offend, if we accept that Siryn is a noirish or Bogart-ian heroine. Final confirmation of this line of interpretation will come if David actually shows us how Siryn finds and "re-pays" her original assailant in future issues.

Rather than a weak-damsel story, Peter David wants us to read X-Factor #5 as if it were an episode in the comic-book version of the Saturday Night Live gameshow Quien Es Mas Macho? (Who is More Macho?) And I'm pleased to report that, in the match-up of Siryn vs. Dr. Leery, Siryn es mas macho. She proves herself to be, indeed, muy muy macho.

And, by his own admission, Siryn's got Rictor beat, too.

Saturday, March 25, 2006

2 Visual Quotations

There's a lot going on in X-Factor #5, and I'm going to try write a coherent post which doesn't spoil the issue. Rather than provide a review, what I'd like to do is point out several interesting visual references that I caught while I was reading.

First of all, that's a nice cover. I'm a big fan of Ryan Sook's; I loved his work on the Seven Soldiers: Zatanna series, and was bummed out when I learned that his run on X-Factor would be a brief one.

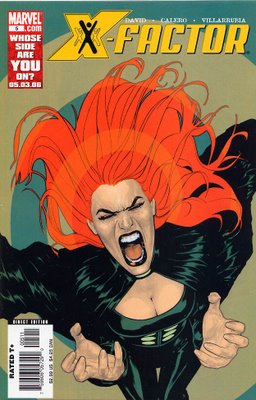

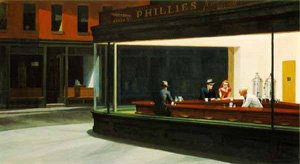

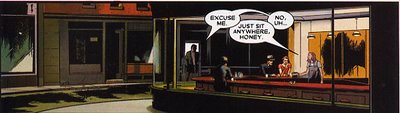

The interior art is by Dennis Calero, and the comic's first panel provides a nice visual reference to Edward Hopper's magnificent 1942 painting Nighthawks, which is at the Art Institute of Chicago. Here's a reproduction:

And here's Calero's "citation" of the painting from X-Factor:

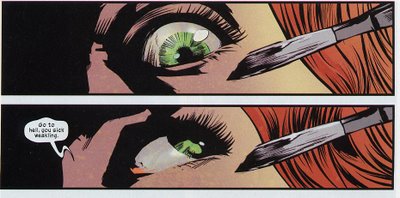

The second visual citation I caught in the book refers to a well-known panel from True Crime Comics #2, (which served as a centerpiece in Dr. Fredric Wertham's Senate testimony in which he advocated the censoring of comics).

This intense and shocking drawing is from a story by Jack Cole titled "Murder, Morphine, and Me: The True Confessions of a Dope Smuggler by Mary Kennedy," which is reproduced in Art Spiegelman and Chip Kidd, Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to Their Limits!, (Chronicle Books, 2001). (It's subsequently revealed that Mary has only dreamed the horrific event that's being depicted in the panel.)

Man, that's an utterly effective image, (which itself refers to Buñel and Dali's Un Chien Andalou). It gets right to the core of our primal fear of being blinded and/or having or eyes punctured. And, since I'm on the topic of visual quotations, let me add another: just before he blasts her to death in Crisis on Infinite Earths #7, the Antimonitor grabs Supergirl's face, framing one of her eyes in the same way.

Man, that's an utterly effective image, (which itself refers to Buñel and Dali's Un Chien Andalou). It gets right to the core of our primal fear of being blinded and/or having or eyes punctured. And, since I'm on the topic of visual quotations, let me add another: just before he blasts her to death in Crisis on Infinite Earths #7, the Antimonitor grabs Supergirl's face, framing one of her eyes in the same way.Finally, here are the two panels from X-Factor #5 that also "quote" Cole's memorable one:

Calero's art and Peter David's writing operate in perfect synch, here. In the first panel, the expression in Siryn's eye conveys fear as she focuses on the scalpel; in the second, it registers her utter contempt as she shifts her attention to her captor.

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

Bin Diving

I stopped in at a comic shop that I don't normally frequent this weekend, and was pleased to find that they have five massive 25c bins. I only had time to make my way through three of them, and those were filled with good stuff.

I made off with:

Alias, nos. 4, 11, 13 & 15.

Animal Man nos. 23 & 25

Artemis Requiem #3.

Avengers #73, "The Search for She-Hulk," part 2 (penned by G. Johns).

Doom Patrol #13 (pencilled by Seth Fisher).

The Question, nos. 2, 3, and 5 (of 6).

Suicide Squad, #50 (There's a zombie thing going on.)

Zatanna: Come Together #3-4 (of 4).

I was especially delighted to find the issues from Grant Morrison's Animal Man run, and the stray Doom Patrol issue with Seth Fisher as "Guest Artist." As I added them to my pile, I thought to myself:

Sweet Fancy Moses, what's the world coming to! These three comics should be kept in climate-controlled glass cases protected by armed guards, not tossed into 25c bins.

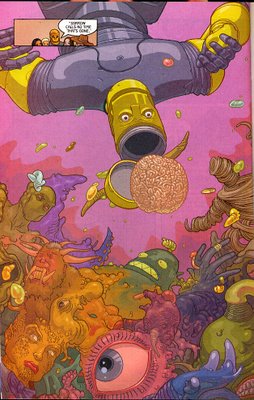

Aside from the images made available around the web when Seth Fisher's death was announced, I was not familiar with his work. I'm happy to say that I am now. Doom Patrol #13 is a visual delight (and the writing by John Arcudi is nice, too.)

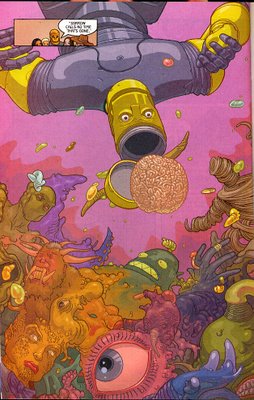

Here's my favorite page:

All I can do is repeat what's been said: Seth Fisher was a very talented young artist who died much too soon.

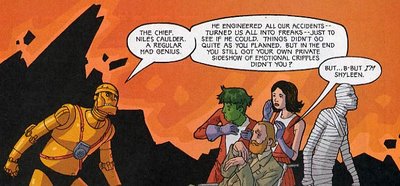

The issue provides a compressed history of the original DP in four panels (take that, All Star Superman!), and things really get interesting when the new members of the patrol (slackers all) find themselves inexplicably inhabiting the bodies of the old, long-gone members while the Brotherhood of Evil is pissed that they have failed to respond to their demands (which were never received in the first place).

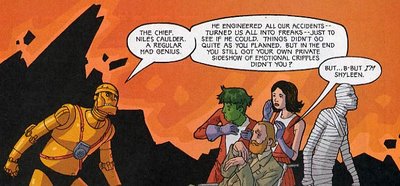

Shyleen, a fashionable, avid shopper (who opened the comic by asking a teammate if her outfit made her look fat), finds herself transformed into the chief.

Kalinara, this panel is for you:

I made off with:

Alias, nos. 4, 11, 13 & 15.

Animal Man nos. 23 & 25

Artemis Requiem #3.

Avengers #73, "The Search for She-Hulk," part 2 (penned by G. Johns).

Doom Patrol #13 (pencilled by Seth Fisher).

The Question, nos. 2, 3, and 5 (of 6).

Suicide Squad, #50 (There's a zombie thing going on.)

Zatanna: Come Together #3-4 (of 4).

I was especially delighted to find the issues from Grant Morrison's Animal Man run, and the stray Doom Patrol issue with Seth Fisher as "Guest Artist." As I added them to my pile, I thought to myself:

Sweet Fancy Moses, what's the world coming to! These three comics should be kept in climate-controlled glass cases protected by armed guards, not tossed into 25c bins.

Aside from the images made available around the web when Seth Fisher's death was announced, I was not familiar with his work. I'm happy to say that I am now. Doom Patrol #13 is a visual delight (and the writing by John Arcudi is nice, too.)

Here's my favorite page:

All I can do is repeat what's been said: Seth Fisher was a very talented young artist who died much too soon.

The issue provides a compressed history of the original DP in four panels (take that, All Star Superman!), and things really get interesting when the new members of the patrol (slackers all) find themselves inexplicably inhabiting the bodies of the old, long-gone members while the Brotherhood of Evil is pissed that they have failed to respond to their demands (which were never received in the first place).

Shyleen, a fashionable, avid shopper (who opened the comic by asking a teammate if her outfit made her look fat), finds herself transformed into the chief.

Kalinara, this panel is for you:

Monday, March 20, 2006

Many Wonder Women, IV

First, a vital piece of information which bubbled to the surface during the "DCU: One Year Greater" panel at Wizard World LA (via Newsarama):

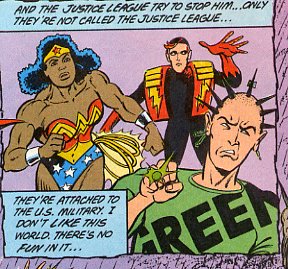

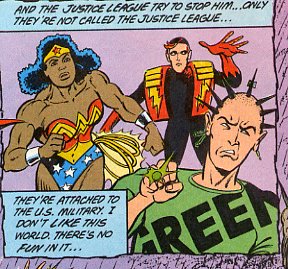

Finally, a favorite panel from Grant Morrison's run on Animal Man (#23; 1990). The issue is titled "Crisis," and the story involves the Psycho-Pirate's efforts to bring back the multiverse.

On page four, Psycho-Pirate explains to a resurrected Ultraman: You didn't die. Nothing really dies. You were right here. In my head all the time. I'm the only one who remembered the way it was before. And now you're back. You're all coming back.

Giving new meanings to the often joined words "Amazon" and "sister," here's a glimpse of an alternate reality Wonder Woman:

(And that's one funky Green Lantern, too.)

Being an optimist, I'm hoping that this Wonder Woman will also make an appearance in one of the remaining issues of Infinite Crisis.

Q: Are there plans for new All-Star books?

A: Yes.

Q: Is All-Star Wonder Woman on the way?

A: See previous question.

Finally, a favorite panel from Grant Morrison's run on Animal Man (#23; 1990). The issue is titled "Crisis," and the story involves the Psycho-Pirate's efforts to bring back the multiverse.

On page four, Psycho-Pirate explains to a resurrected Ultraman: You didn't die. Nothing really dies. You were right here. In my head all the time. I'm the only one who remembered the way it was before. And now you're back. You're all coming back.

Giving new meanings to the often joined words "Amazon" and "sister," here's a glimpse of an alternate reality Wonder Woman:

(And that's one funky Green Lantern, too.)

Being an optimist, I'm hoping that this Wonder Woman will also make an appearance in one of the remaining issues of Infinite Crisis.

Saturday, March 18, 2006

Jessica Abel, II

La Perdida, (Pantheon Books, 2006)

275 pp. + Glossary; $19.95

Jessica Abel's bracing graphic novel La Perdida is a suspenseful, well-drawn book. Her visual style is nuanced: her versatile brush is equally effective at depicting individual expressions, outdoor and crowd scenes, and fast-moving action. Her skillful writing doesn't take a back seat to the art, either: this is a page-turning narrative driven by the decisions, choices, and actions of the book's central female character.

Carla, the half-Mexican American expatriate who carves out a precarious life over a year spent in Mexico City, has an almost tangible need for her Mexican identity to be recognized, confirmed, and re-inforced -- and she most needs (and wants) this recognition and reinforcement to come from Mexicans, the people who matter most to her. She progressively isolates herself from other expatriates who might offer her advice, assistance, or guidance--and she does this for no other reason than that they are Americans. As she labors to form an identity that will be acceptable to her newly acquired Mexican friends, Carla's rejection of her American-ness and her need for recognition become the prime movers of the novel's action.

Carla is childish; a poor judge of character; judgmental; passive-aggressive; willful; misguided; noisy and belligerent when drunk; and a disaster waiting to happen. The novel culminates with her trapped in an unpleasant, life-threatening situation which a mildly perceptive person would easily have avoided. And though I spent most of the book angered by the bad choices that she was making, I strongly empathized with her nonetheless.

Solzhenitsyn wrote (in The First Circle, I think) that the soul is not granted to us, but rather, it's something that each of us must make. I interpret him to have been speaking about our identities, which we form on a personal level (though we do so in relation to our families, cultures, communities, and our nationalities). My parents were the sole members of their families who emigrated to the US. They dissuaded my sister and I from speaking Spanish, while sending us to all-white parochial schools. So, I understand, on a fairly profound level, Carla's grappling to forge her own tenuous sense of self.

Rather than forge anything, most of us scrounge and cobble; Carla, however, flails. She heaps scorn upon the other Americans she meets in Mexico City. She becomes friends with an annoying Marxisant blow-hard named Memo. Although he hates the US and its tourists, this hatred is not a bar to his tireless attempts to sleep with any attractive American tourist or student with whom he might come into contact. Memo becomes Carla's "mentor" in Mexican-ness, or, rather, he's the relentless castigator of her American-ness, administering verbal bludgeonings that she both hates and craves. However, Memo's frequent tongue-lashings ensure that Carla can never stand as her new friend's moral equal or compatriot.

Carla's rejection of the community of American expatriates in Mexico City becomes complete when she sets up house with Memo's young and pretty friend Oscar, a shiftless low-level T-shirt peddler, pot dealer, and aspiring DJ, who in turn places Carla in situations that include a man named El Gordo, who is decidedly bad news. Memo's harangues lead to Carla's constant self-abasement (please like me; can't you see I'm one of you?), and allow Memo and Oscar to take economic advantage of her without their feeling the need to justify or even explain themselves.

There's a fair amount of physical violence in the last portion of the book--Carla is essentially held prisoner in her home, and she finds herself at the mercy of several brutal characters who have no constraints against striking someone weaker than themselves. The situation is a dire one, and its severity leads her to finally assess things with some much-needed clarity.

While the final portion of the book makes for an intense reading experience, it's a testament to Abel's skill that the force of the later material is matched by a scene that takes place much earlier in the book. Prior to actually visiting Mexico, Carla had formed a strong identification with Frida Kahlo--the painter's life had come to represent something essential about Mexico to which she could connect from the States. Predictably, Memo finds Carla's fascination with Mexican crafts, and specifically with Kahlo's life and painting, as touristic and decadently bourgeoise.

Here is the culmination of their argument:

Man, that's powerful writing and effective use of imagery. By showing us Memo goading Carla into tearing the poster of Frida, Abel provides a single moment of revelatory dramatic force: we learn something essential about both of the characters. Several such moments punctuate this remarkable novel.

Rather than a narrative that follows a young heroine as she builds a sense of her Mexicanidad, Abel's novel instead charts the destruction of Carla's sense of self, which makes for compelling and difficult reading. In my initial post about Abel, I mentioned that La Perdida could be translated as The Lost Woman. The text to the novel's final panels reinforces this translation. Carla, back home in Chicago, ruminates about her experience:

After she's back home, when the dust has settled, Carla yearns to find an illusory person -- the girl she believes she was prior to her experiences in Mexico. Ironically, that person is tied to her youthful idea of Mexico, something which no longer exists for her, given the reality of her harsh experience in Mexico. Carla was lost, and has also suffered a loss. (Talk about lightning striking twice.)

Jessica Abel has produced a taut and intense first novel, and I look forward to reading whatever she produces in the future.

275 pp. + Glossary; $19.95

Jessica Abel's bracing graphic novel La Perdida is a suspenseful, well-drawn book. Her visual style is nuanced: her versatile brush is equally effective at depicting individual expressions, outdoor and crowd scenes, and fast-moving action. Her skillful writing doesn't take a back seat to the art, either: this is a page-turning narrative driven by the decisions, choices, and actions of the book's central female character.

Carla, the half-Mexican American expatriate who carves out a precarious life over a year spent in Mexico City, has an almost tangible need for her Mexican identity to be recognized, confirmed, and re-inforced -- and she most needs (and wants) this recognition and reinforcement to come from Mexicans, the people who matter most to her. She progressively isolates herself from other expatriates who might offer her advice, assistance, or guidance--and she does this for no other reason than that they are Americans. As she labors to form an identity that will be acceptable to her newly acquired Mexican friends, Carla's rejection of her American-ness and her need for recognition become the prime movers of the novel's action.

Carla is childish; a poor judge of character; judgmental; passive-aggressive; willful; misguided; noisy and belligerent when drunk; and a disaster waiting to happen. The novel culminates with her trapped in an unpleasant, life-threatening situation which a mildly perceptive person would easily have avoided. And though I spent most of the book angered by the bad choices that she was making, I strongly empathized with her nonetheless.

Solzhenitsyn wrote (in The First Circle, I think) that the soul is not granted to us, but rather, it's something that each of us must make. I interpret him to have been speaking about our identities, which we form on a personal level (though we do so in relation to our families, cultures, communities, and our nationalities). My parents were the sole members of their families who emigrated to the US. They dissuaded my sister and I from speaking Spanish, while sending us to all-white parochial schools. So, I understand, on a fairly profound level, Carla's grappling to forge her own tenuous sense of self.

Rather than forge anything, most of us scrounge and cobble; Carla, however, flails. She heaps scorn upon the other Americans she meets in Mexico City. She becomes friends with an annoying Marxisant blow-hard named Memo. Although he hates the US and its tourists, this hatred is not a bar to his tireless attempts to sleep with any attractive American tourist or student with whom he might come into contact. Memo becomes Carla's "mentor" in Mexican-ness, or, rather, he's the relentless castigator of her American-ness, administering verbal bludgeonings that she both hates and craves. However, Memo's frequent tongue-lashings ensure that Carla can never stand as her new friend's moral equal or compatriot.

Carla's rejection of the community of American expatriates in Mexico City becomes complete when she sets up house with Memo's young and pretty friend Oscar, a shiftless low-level T-shirt peddler, pot dealer, and aspiring DJ, who in turn places Carla in situations that include a man named El Gordo, who is decidedly bad news. Memo's harangues lead to Carla's constant self-abasement (please like me; can't you see I'm one of you?), and allow Memo and Oscar to take economic advantage of her without their feeling the need to justify or even explain themselves.

There's a fair amount of physical violence in the last portion of the book--Carla is essentially held prisoner in her home, and she finds herself at the mercy of several brutal characters who have no constraints against striking someone weaker than themselves. The situation is a dire one, and its severity leads her to finally assess things with some much-needed clarity.

While the final portion of the book makes for an intense reading experience, it's a testament to Abel's skill that the force of the later material is matched by a scene that takes place much earlier in the book. Prior to actually visiting Mexico, Carla had formed a strong identification with Frida Kahlo--the painter's life had come to represent something essential about Mexico to which she could connect from the States. Predictably, Memo finds Carla's fascination with Mexican crafts, and specifically with Kahlo's life and painting, as touristic and decadently bourgeoise.

Here is the culmination of their argument:

Man, that's powerful writing and effective use of imagery. By showing us Memo goading Carla into tearing the poster of Frida, Abel provides a single moment of revelatory dramatic force: we learn something essential about both of the characters. Several such moments punctuate this remarkable novel.

Rather than a narrative that follows a young heroine as she builds a sense of her Mexicanidad, Abel's novel instead charts the destruction of Carla's sense of self, which makes for compelling and difficult reading. In my initial post about Abel, I mentioned that La Perdida could be translated as The Lost Woman. The text to the novel's final panels reinforces this translation. Carla, back home in Chicago, ruminates about her experience:

And I look at her, the girl I was. Her head full of plans and hopes for what might lie in her future.However, there's a second possible translation of La Perdida, which is The Lost Thing, or simply, The Loss. Here's text from a few panels in the novel's prologue that matches this translation:

And I watch her. I watch her take one step, two steps.

And then she takes a turn down an obscure and unmarked path. I struggle to keep track of her as she fades from view. Before I know it, she's gone from sight, from understanding.

She's lost.

I can't shake the feeling that I've ruined something precious.Like I said, Abel's writing is as good as her art.

That I lost something there. I want to search for it.

But I'm an exile. I can never go back.

After she's back home, when the dust has settled, Carla yearns to find an illusory person -- the girl she believes she was prior to her experiences in Mexico. Ironically, that person is tied to her youthful idea of Mexico, something which no longer exists for her, given the reality of her harsh experience in Mexico. Carla was lost, and has also suffered a loss. (Talk about lightning striking twice.)

Jessica Abel has produced a taut and intense first novel, and I look forward to reading whatever she produces in the future.

Thursday, March 16, 2006

Wondrous Science

Item 1:

The US military is working to develop squadrons of "smart" insects for military purposes. From the BBC article, Pentagon Plans Cyber-Insect Army:

I thought these Darpa guys were supposed to be science-fiction-reading nerds. Can they not see that implementing this plan will inevitably lead to a dystopian future? Butterflies guiding bombs? It seems clear to me that this'd be an obvious heralding of the apocalypse.

The article also includes this handy rundown of several notable deployments of animals during war-time (which pretty much left me speechless):

Item 2:

Courtesy of the NY Times, meet Kiwa hirsuta.

From the article:

Now, while I'd never want to ingest a kiwa, I could see myself buying a well-made plush toy that looked like one.

The US military is working to develop squadrons of "smart" insects for military purposes. From the BBC article, Pentagon Plans Cyber-Insect Army:

Darpa believes scientists can take advantage of the evolution of insects, such as dragonflies and moths, in the pupa stage.

"Through each metamorphic stage, the insect body goes through a renewal process that can heal wounds and reposition internal organs around foreign objects," its proposal document reads.

The foreign objects it suggests to be implanted are specific micro-systems - Mems - which, when the insect is fully developed, could allow it to be remotely controlled or sense certain chemicals, including those in explosives.

The invasive surgery could "enable assembly-line like fabrication of hybrid insect-Mems interfaces", Darpa says.

I thought these Darpa guys were supposed to be science-fiction-reading nerds. Can they not see that implementing this plan will inevitably lead to a dystopian future? Butterflies guiding bombs? It seems clear to me that this'd be an obvious heralding of the apocalypse.

The article also includes this handy rundown of several notable deployments of animals during war-time (which pretty much left me speechless):

WWII: Attach a bomb to a cat and drop it from a dive-bomber on to Nazi ships. The cat, hating water, will "wrangle" itself on to enemy ship's deck. In tests cats became unconscious in mid-air

WWII: Attach incendiaries to bats. Induce hibernation and drop them from planes. They wake up, fly into factories etc and blow up. Failed to wake from hibernation and fell to death

Vietnam War: Dolphins trained to tear off diving gear of Vietcong divers and drag them to interrogation, sources linked to the programme say. Syringes later placed on dolphin flippers to inject carbon dioxide into divers, who explode. US Navy has always denied using mammals to harm humans

Item 2:

Courtesy of the NY Times, meet Kiwa hirsuta.

From the article:

Kiwa hirsuta ... represents not just a new species or even a new genus ... but a family of animals previously unknown to science. The researchers were cruising the South Pacific last year, hundreds of miles south of Easter Island, using the submersible vehicle Alvin to study the strange creatures that live along cracks in the sea floor called hydrothermal vents.

Despite their extreme heat and sulfurous gases, these vents teem with bizarre bacteria, worms, clams and other creatures. In fact, many scientists theorize that life on earth began at these vents. ... Because it looked like the abominable snowman of crustaceans, they called it the "Yeti crab." The aquarium said its family name, Kiwaidae, comes from Kiwa, a Polynesian goddess of crustaceans. The creature is blind, and its hairs — really the kind of bristles found on moths or bumblebees — are colonized by bacteria organized in filaments.

Now, while I'd never want to ingest a kiwa, I could see myself buying a well-made plush toy that looked like one.

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

Jessica Abel, I

Jessica Abel's La Perdida has just been published in a handsome hardcover edition by Pantheon Books. I've been aware of Abel's work for some time, and have read some of the middle issues of the comic that forms the basis of the novel. Although La Perdida (The Lost One, or The Lost Woman) sounds like it could be a place name, here it actually serves as an adjective that perfectly describes Carla, the book's compelling central character. I've only just finished it, and will post a review when I've given it more thought and have spent more time with it.

Abel was recently interviewed in The Comics Journal (#270 August 2005; excerpts here). She comes across as a thoughtful and interesting artist, and I have to admit I was intrigued and won over by her.

Two things in particular deserve mention:

First of all, she's very much committed to the teaching of cartooning; (the dust-jacket of La Perdida mentions that she's collaborating on a textbook about making comics).

This exchange with Greg Stump from TCJ interview gets to the heart of her deeply-felt point of view:

Stump: The one reason I bring it up is I was talking to Jim Woodring about this, because I teach kids -- not older kids, but little kids. He was talking about James Sturm's new school that's starting up, and he asked me if I would contemplate trying to do something like that ... But he was pretty opposed to the idea that you could teach a cartoonist, or a cartoonist could be taught, and he said it was like saying you could teach someone to be a poet or something like that.

Abel:I absolutely disagree with that point of view. I think it's a really common attitude for cartoonists to have, especially for cartoonists of his generation and older, and even more so for ones who had to go out on their own to do what they wanted to do, because they weren't working for Marvel or DC or whatever. That's what they did, they think that the only way to learn to be a cartoonist is to just flail around until you get someplace or, more likely, don't.

I really disagree. I'm very proud to say that my students do not come out of my class looking like me, none of them have. They come out looking more like themselves. I think I can teach them a lot of stuff. I can't teach them to be artists; I can't teach them the central spark.

Stump: That may be what he was describing.

Abel: I think he's saying you can't teach people -- for example, if you say can't teach people how to be poets. Well, you can actually teach people how to be poets. You can't teach them to be great poets, but you can teach them how to write, how to think, many things about structure, and the concerns that might be in poetry. You can teach them to look at other poems.

Stump: You can certainly expose people to work that's going to transform their understanding...

Abel: That's at a minimum. You can do a lot more than that. You can be taught how to write. You can be taught how to draw. You can teach somebody how to draw from life and how to draw from their imagination. I don't plan to do that, but it can be done. I think saying it can't be taught has a destructive influence on our world of art. It's a bad idea, that everybody has to individually struggle along on their own, and end up wherever they end up. For hundreds of thousands of years, artists have worked as apprentices. It's only in the last 50 that they haven't. And working as an apprentice is learning from the master -- copying, nothing wrong with copying for a while. I don't teach my students as if they're apprentices. I don't have them copy me and just do my grunt work, but I think that's one model for education that works.

You can tell, I'm getting a little heated. I don't like the idea that somebody like Woodring would say that it's a bad idea to teach comics. If somebody had said to me when I was 21, when I knew I wanted to be a cartoonist, "Hey, there's a place where they're good teachers and you could really learn," like James' school, that would have been magic. I don't know if I could have or would have done it in terms of money and so on, but it could have gotten me to where I am now, six years earlier. Why should I suffer? Why should I have to reinvent the wheel over and over again?

....

Stump: I think he didn't really study so much as he learned when he was working in animation or something like that.

Abel: When he was an apprentice.

Stump: Yeah, exactly, right.

Abel: That's the attitude I'm fighting against. Part of our proposal for our book is specifically addressing that prejudice, and I think it is a prejudice. It's very much the Modernist ideal, the individual artist off in his or her garret struggling alone. That model is destructive and self-destructive. I don't think you come up with better art because of that. The myth is that it's the only way you come up with true, pure art, but I just don't buy it.

Our argument in our pitch for our book is that group learning is the best way. It's not the only way, and we will accommodate people who want to learn on their own, but our emphasis and our push all the way through the book is going to be: If students don't have the opportunity to go to a class with a teacher, encourage them to form groups and work together. Having feedback and having people look at your work and having other minds to help you think through problems, that will get you years ahead. Why struggle when you don't have to?

Why, indeed.

Abel's second winning characteristic, (fully as admirable as the first I mentioned), is her acknowledgement of the influence of Wonder Woman. This section of the interview does not appear in the online excerpt:

Stump: You said that Love and Rockets was one of your first major influences.

Abel: ... Basically, Wonder Woman was my strongest early influence. ... I love Wonder Woman, but I really love Wonder Woman when Charles Moulton was writing her, and Harry Peters was drawing her. [Stump laughs.] Because Harry Peters' drawing style is so fucking weird. It's so awesome.

Stump: I can't picture it in my head at the moment.

Abel: The drawings look like woodcuts. ... Peters' style is crazy weird. Bad anatomy, really enthusiastic and cool and very modernist-looking to me. I really like it, but it's also sort of medieval. ... [M]ost of the early Wonder Woman stuff is meant to prove that women are superior to men. If we only just recognized it in ourselves, we're better than men, which is funny. Wonder Woman's from Paradise Island or whatever, where men aren't even allowed to be at all. There's all these plotlines about women-haters, men who deny women opportunity to achieve academically or whatever because they hate women, they don't think they're worthwhile. So she and her sidekicks from this girls' college go and kick somebody's ass. ... And that's the plot. It's just unbelievably weird. There's one where there's this kind of mentalist guy who creates goop out of the air and makes it turn into George Washington and talk to people.

Stump: You remember these pretty clearly.

Abel: Because I read this one book 18,000 times. I now have this DC collection of early Wonder Woman stuff, which is also excellent. But the collection I've always had is one that Ms. Magazine put out, for obvious reasons, in the early '70s. They're all stories from the '40s, a selection of what Gloria Steinem liked the best. ... My mom or one of her feminist friends gave me the book when I was like four, a little kid. ... It deeply impressed me, and now looking at it as an adult, it impresses me still because it's really inventive and exciting. I have the DC collection of early Superman, and that stuff's fucking boring -- those stories are boring. Wonder Woman stories are not boring. They're fun. That's just a quality-of-writing thing, it's not only because I love Wonder Woman. They're really better stories. They're much more entertaining, and they're drawn better. Unfortunately, DC recolored everything, so they've lost that other thing that got imprinted on me early. The Ms. book is a photographic reproduction of the bad coloring from the '40s. Or maybe they just recolored it badly, I don't know, but it's all off-register and everything that's supposed to be gray is purple and it's weird and awesome. Those things tie in at a basic, four-year-old level in my aesthetics.

These are but a small helping of the insights contained in Abel's interview, which I've been re-reading and working through since August. (For those so inspired, back issues of The Comics Journal are available, here.)

You can join Jessica Abel's ass-kicking Artbabe Army, here.

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

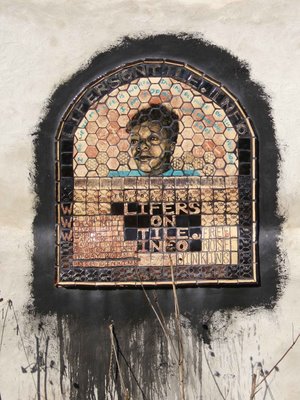

Neighborhood Art

I've always admired this mosaic. It caught my eye during my first walk in the neighborhood, and I pass it frequently, as it's placed on the side of a building quite close to my local coffee shop.

I photographed it this afternoon, and have only just now realized that it contains a text component.

Here's what's written on the lower left:

I believe that my life is worth saving because of the person I am today. 2003 Rose Dinkins

Lower right:

Free Rose Dinkins

Rose Dinkins, it seems, is one of the Lifers on Tile.

Due to the expression of the figure's eyes, I had always assumed it was a death memorial. Though I wasn't entirely right, perhaps I wasn't too far off the mark, either.

Update 1.15.07:

A helpful reader has provided me with details on the artist, Mary DeWitt, additional information on Rose Dinkins, and context for the Lifers on Tile.

Here are the links:

http://web.archive.org/web/20040109220933/http://lifersontile.info/

http://marydewitt.net/13925.html

Thanks AR!

Monday, March 13, 2006

Schizo #4

The fourth issue of Ivan Brunetti's comic Schizo has been published by Fantagraphics, and it's a tabloid-sized collection of masterful cartoons drawn by the artist between December 1999 and July 2005. Schizo #3 was first printed way back in 1998 (a second printing appeared in 2003), so the series is on an open-ended publication schedule that refuses, as the author says, to "conform to Euclidean timespace."

Words that describe Brunetti's cartoons from issues 1-3:

Angry; surreal; hyper-violent; self-absorbed; self-lacerating; sexually explicit; misanthropic; misogynistic; offensive; scabrous; scatalogical; suicide- and death-obsessed; and really, really, really funny.

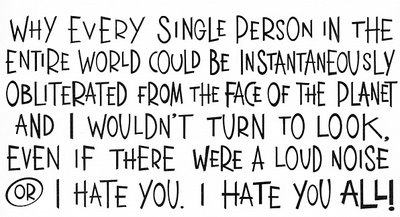

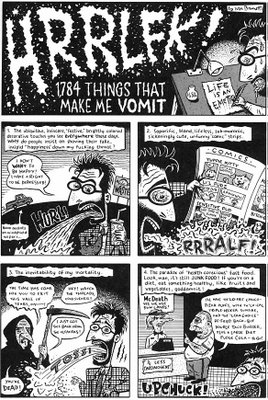

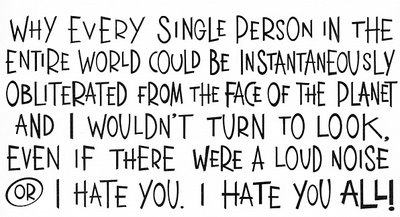

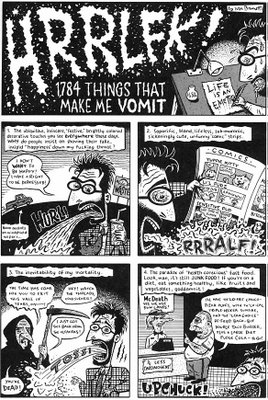

As an introduction to the "tone" of Schizo, here's the title splash from issue #1:

Yes, that's the title of the strip that follows. And here's the first page of the strip which closes the collection:

Yes, that's the title of the strip that follows. And here's the first page of the strip which closes the collection:

I first learned of Brunetti's work by reading an interview conducted by Gary Groth that appeared in The Comics Journal #264 in December, 2004. (An excerpt of the interview is available here.) This was one of the most compelling pieces dealing with an individual's creative process that I'd ever read.

Extended excerpts:

So what's my verdict on Brunetti's post-Schizo #3 cartoons?

Many of the strips are very funny, most are thoughtful, and several of them are sublime.

"Whither Shermy?" an homage to Charles Shulz printed on the comic's outside wrapper, and the untitled strip appearing on the reverse page, both evince Brunetti's deep understanding of how cartoons work. The first utilizes a strict, repetitive "four box" structure (itself a homage to Shulz), but blends interesting images and a dense text to make this a thoughtful, memorable strip. The second, (accessible at Brunetti's website here), is an autobiographical depiction of a morning in the artist's life. Brunetti allows the shape of the house to structure and limit individual frames, as well as direct the narrative flow.

The strips that I especially liked were the biographical ones: "P. Mondrian," "S. Kjerkegaard," and "Erik Satie: Compositeur de Musique," previously appeared in McSweeney's Quarterly Concern #13 (2004). "Francoise Hardy," "Louise Brooks," and "Joris-Karl Huysmans" appear here for the first time (that I'm aware of).

The biographical strips are, of course, actually about Brunetti. (As is "Whither Shermy?", too.) He has chosen to depict particular individuals, and specific moments in their lives, because of who he is, how he feels about life, and what he wants to "tell" us about this. However, in choosing subjects that are (by definition) outside of himself, Brunetti produces effective cartoons that are less inward-looking and, I think, more effective.

My favorite, "Louise Brooks," is available online at Brunetti's own website, here. It works on many different levels, combining an interesting life with the subject's iconic "look"--her hairstyle perfectly matches his drawing style. Most importantly, Brunetti provides a humane and empathetic portrayal of Brooks' life experience, even allowing her to speak the strip's final words. (Several of the other biographical subjects are depicted bleakly, on their deathbeds, in their strip's final panel.)

This past fall Brunetti curated a show at Columbia College in Chicago titled "The Cartoonist's Eye." (Milo George provided a nice description of the exhibit at Tom Spurgeon's The Comics Reporter site.) An adjunct to that show is Brunetti's forthcoming book, An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories, (Yale University Press), which will be published in October. I'll be on the look-out for it.

Words that describe Brunetti's cartoons from issues 1-3:

Angry; surreal; hyper-violent; self-absorbed; self-lacerating; sexually explicit; misanthropic; misogynistic; offensive; scabrous; scatalogical; suicide- and death-obsessed; and really, really, really funny.

As an introduction to the "tone" of Schizo, here's the title splash from issue #1:

Yes, that's the title of the strip that follows. And here's the first page of the strip which closes the collection:

Yes, that's the title of the strip that follows. And here's the first page of the strip which closes the collection:

I first learned of Brunetti's work by reading an interview conducted by Gary Groth that appeared in The Comics Journal #264 in December, 2004. (An excerpt of the interview is available here.) This was one of the most compelling pieces dealing with an individual's creative process that I'd ever read.

Extended excerpts:

Brunetti: I remember being a really angry person at that time, and that really gave me a lot of energy. And I just cannot get that back. I'm just not that angry a person any more. I'm not that repressed a person any more, either. I was really repressed.

Groth: Do you think that putting this all on paper was a way of breaking through that repression?

Brunetti: Totally. Yeah. ... It was like a "healing" process. That's what I see it as now. It wasn't even art. To me it's not even art. It's just therapy.

Groth: Well, we don't want you to be too healed. ... You said you were full of anger ...

Brunetti: Kind of undefined. I'm not someone who would start fights in a bar, or something like that, but it's just a lot of repressed anger. I think all my life I'd repressed how angry I was. That's what it was.

Groth: But that anger it seems to me is still on display in Schizo #2 and #3.

Brunetti: Yeah, it didn't get much better. Schizo #3 is not so angry ... At that point, I think I knew how to laugh a little bit at myself ... I knew my excesses. ...It's hard for me to look at the first two issues, Gary. It's like I can't even read them. The second issue especially, is completely insanne. I was out of my mind. Out of my mind.

....

Groth: Were you more confident doing Schizo #1, #2 and #3, than you were doing work post Schizo #3?

Brunetti: I think the anger gave me some kind of arrogance.

Groth: Fueled you.

Brunetti: It did. ... It was fueling me, and then I was communicating that, and I got it out of my system, and now, I'm just exploring other parts of myself. And those things are much more painful than expressing my anger because now, I've really been delving into how sad and depressed I've been ... The weird thing is I'm still trying to make people laugh. ... That's important to me.

So what's my verdict on Brunetti's post-Schizo #3 cartoons?

Many of the strips are very funny, most are thoughtful, and several of them are sublime.

"Whither Shermy?" an homage to Charles Shulz printed on the comic's outside wrapper, and the untitled strip appearing on the reverse page, both evince Brunetti's deep understanding of how cartoons work. The first utilizes a strict, repetitive "four box" structure (itself a homage to Shulz), but blends interesting images and a dense text to make this a thoughtful, memorable strip. The second, (accessible at Brunetti's website here), is an autobiographical depiction of a morning in the artist's life. Brunetti allows the shape of the house to structure and limit individual frames, as well as direct the narrative flow.

The strips that I especially liked were the biographical ones: "P. Mondrian," "S. Kjerkegaard," and "Erik Satie: Compositeur de Musique," previously appeared in McSweeney's Quarterly Concern #13 (2004). "Francoise Hardy," "Louise Brooks," and "Joris-Karl Huysmans" appear here for the first time (that I'm aware of).

The biographical strips are, of course, actually about Brunetti. (As is "Whither Shermy?", too.) He has chosen to depict particular individuals, and specific moments in their lives, because of who he is, how he feels about life, and what he wants to "tell" us about this. However, in choosing subjects that are (by definition) outside of himself, Brunetti produces effective cartoons that are less inward-looking and, I think, more effective.

My favorite, "Louise Brooks," is available online at Brunetti's own website, here. It works on many different levels, combining an interesting life with the subject's iconic "look"--her hairstyle perfectly matches his drawing style. Most importantly, Brunetti provides a humane and empathetic portrayal of Brooks' life experience, even allowing her to speak the strip's final words. (Several of the other biographical subjects are depicted bleakly, on their deathbeds, in their strip's final panel.)

This past fall Brunetti curated a show at Columbia College in Chicago titled "The Cartoonist's Eye." (Milo George provided a nice description of the exhibit at Tom Spurgeon's The Comics Reporter site.) An adjunct to that show is Brunetti's forthcoming book, An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories, (Yale University Press), which will be published in October. I'll be on the look-out for it.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

Huntress+Church

Helena Bertinelli appeared briefly in Infinite Crisis #5; she's got two small panels on page two, and is mentioned by Alex Luthor during his info-dumping conversation with the Psycho-Pirate later in the book. (Where it's revealed that if the multiverse had continued to evolve, Helena B. would have been born on Earth-8. Thanks, Alex; many a night's sleep has been lost due to my inabilty to even formulate that question.)

Being an academic, my eyes automatically scanned down to the bottom of page two (perhaps I was looking for footnotes). Noting the end of the church scene, with some Earth-2 stuff following on page 3, I then prepared to actually read the page. However, my eye caught Huntress's close-in panel at the bottom, punctuated by her "Amen" word balloon. Though I was just skimming at that point, my first thought was: Damn you Geoff Johns! Damn you to hell, sir!

Let me explain why I flew off the handle like that. As a comics reader (or reader of any kind of fiction, I suppose), points of identification with characters are crucial, and one of my ways of identifying with (and understanding) Helena Bertinelli is through her complicated relationship to her Catholicism.

Here are two panels from Birds of Prey #72 that brought this all into focus for me:

(Just to fill you in, Helena and Vixen have infiltrated a church that has proven greatly attractive to young high schoolers, several of whom, however, have committed suicide while dressed up as their favorite superheroes.)

Now while I'd kill myself if I ever handled a crossbow, I was raised Catholic. Huntress' "I'm not too crazy about churches in general" line was a hook that linked me to the character; the "offends even me" coda subtly signalled that she still wrestles with her relationship to the religion in which she was brought up.

All I can say is, man, that Gail Simone sure knows how to write a comic book.

So, when my eye scanned down to the bottom of page two of IC #5 and fixed upon Huntress' "Amen" word balloon (it's the single word she speaks), I kind of lost it. It's not that I'm opposed to Huntress ever going to church, saying "amen," or even being reconciled with the Church. What I do oppose is having something central like this occur off panel--I presumed it had happened in the etherial netherworld between Birds of Prey and Infinite Crisis. The other possible explanation, that the horrific events occurring during the crisis had brought Helena fully back to the faith, just didn't feel right to me, either.

However, when I actually read the page, I inwardly retracted the harsh words that I had directed at Mr. Johns. For what Helena Bertinelli is actually saying "amen" to is not the blessing being intoned, but rather Blue Devil's call to action. ("[L]et's get the hell out of here. There's people that need help.") Contrary to my initial, rushed reading, Huntress' utterance of the word is entirely in character.

The close-up in the page's final panel doesn't capture the Huntress in a moment of religious reverence or devotion. Someone has finally said something that she agrees with whole-heartedly. Her eyes convey readiness and determination.

People, she seems to be saying, it's time.

Being an academic, my eyes automatically scanned down to the bottom of page two (perhaps I was looking for footnotes). Noting the end of the church scene, with some Earth-2 stuff following on page 3, I then prepared to actually read the page. However, my eye caught Huntress's close-in panel at the bottom, punctuated by her "Amen" word balloon. Though I was just skimming at that point, my first thought was: Damn you Geoff Johns! Damn you to hell, sir!

Let me explain why I flew off the handle like that. As a comics reader (or reader of any kind of fiction, I suppose), points of identification with characters are crucial, and one of my ways of identifying with (and understanding) Helena Bertinelli is through her complicated relationship to her Catholicism.

Here are two panels from Birds of Prey #72 that brought this all into focus for me:

(Just to fill you in, Helena and Vixen have infiltrated a church that has proven greatly attractive to young high schoolers, several of whom, however, have committed suicide while dressed up as their favorite superheroes.)

Now while I'd kill myself if I ever handled a crossbow, I was raised Catholic. Huntress' "I'm not too crazy about churches in general" line was a hook that linked me to the character; the "offends even me" coda subtly signalled that she still wrestles with her relationship to the religion in which she was brought up.

All I can say is, man, that Gail Simone sure knows how to write a comic book.

So, when my eye scanned down to the bottom of page two of IC #5 and fixed upon Huntress' "Amen" word balloon (it's the single word she speaks), I kind of lost it. It's not that I'm opposed to Huntress ever going to church, saying "amen," or even being reconciled with the Church. What I do oppose is having something central like this occur off panel--I presumed it had happened in the etherial netherworld between Birds of Prey and Infinite Crisis. The other possible explanation, that the horrific events occurring during the crisis had brought Helena fully back to the faith, just didn't feel right to me, either.

However, when I actually read the page, I inwardly retracted the harsh words that I had directed at Mr. Johns. For what Helena Bertinelli is actually saying "amen" to is not the blessing being intoned, but rather Blue Devil's call to action. ("[L]et's get the hell out of here. There's people that need help.") Contrary to my initial, rushed reading, Huntress' utterance of the word is entirely in character.

The close-up in the page's final panel doesn't capture the Huntress in a moment of religious reverence or devotion. Someone has finally said something that she agrees with whole-heartedly. Her eyes convey readiness and determination.

People, she seems to be saying, it's time.

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

Blog Against Sexism: Sor Juana, 1651?-1695

International Women's Day, 2006

I've made several recent posts dealing with problematic gender representations in the arts and inequalities in society, and, rather than do something similar today, I wanted to devote this space to a woman from the past who continues to impress and inspire me. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a remarkable Mexican intellectual who wrote poems, plays, essays, and other learned works, while amassing what was probably one of the largest personal libraries in the Americas. She stands as one of the most accomplished writers of that, or any other, place and time. (A one-volume collection of her works is available in English as a Penguin classics paperback.)

I am convinced that describing and honoring her complex life and achievements is itself an act against sexism.

Though she had found favor as a young woman at the viceregal court, Sor Juana had been born illegitimate, and never lost sight of the particular dangers that unaffiliated young women faced in her society. Consequently, she took religious vows at the end of the 1660s; here's how she later described her decision-making:

In his book, Sor Juana: Or the Traps of Faith, (Harvard UP, 1988), Octavio Paz wrote of this momentous act as follows:

So Sor Juana, a woman from early modern Mexico, actively chose an intellectual life, a life acquired through her choice to embed herself in a religious community. And it's important to note that though she became a nun, Sor Juana never renounced human contact, often convening gatherings of friends and admirers in the public quarters of the the convent after prayers.

In 1690 Sor Juana was attacked in print by an anonymous figure who was clearly protected and abetted by powerful figures within the Mexican Church hierarchy. She was specifically criticized for devoting herself to the production of secular works to the detriment (or avoidance) of religious subjects. Juana responded in kind, defending herself vigorously and thoughtfully in the Respuesta de Sor Filotea, (which has been called the first feminist manifesto).

In the years preceding her death, Sor Juana came under the firm guidance of her confessor, Father Antonio Núñez de Miranda, (a man who scourged himself with such frequency and severity that the walls and door of his room were spattered with his blood). While Mexico-City society was gripped by severe public health and political crises, it appears that Juana decided to move on from her life as a secular writer and embrace another, less public one.

At this same time she undertook an act which reflected her commitment to change, one which forces me to grimace even now as I imagine it: Sor Juana gave up her library, allowing the great majority of her books and scientific instruments to be dispersed and sold for the benefit of the poor. (Without firm evidence, we are left speculate as to whether this act was forced upon Juana, or was effected without coercion, providing yet another example of her considerable will and determination. However, given her inclinations, coercion seems the most likely explanation.)

Let me just repeat that: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz gave up her library.

She died of disease shortly thereafter.

Sor Juana dazzles, inspires, confounds, and mystifies. As an educator, bibliophile, scholar, and student of the past, I consider her to be someone deserving of the highest honor and respect.

In concluding, I can't improve upon what Octavio Paz wrote in the Epilogue to his book:

I've made several recent posts dealing with problematic gender representations in the arts and inequalities in society, and, rather than do something similar today, I wanted to devote this space to a woman from the past who continues to impress and inspire me. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a remarkable Mexican intellectual who wrote poems, plays, essays, and other learned works, while amassing what was probably one of the largest personal libraries in the Americas. She stands as one of the most accomplished writers of that, or any other, place and time. (A one-volume collection of her works is available in English as a Penguin classics paperback.)

I am convinced that describing and honoring her complex life and achievements is itself an act against sexism.

Though she had found favor as a young woman at the viceregal court, Sor Juana had been born illegitimate, and never lost sight of the particular dangers that unaffiliated young women faced in her society. Consequently, she took religious vows at the end of the 1660s; here's how she later described her decision-making:

And so I entered the religious order, knowing that life there entailed certain conditions (I refer to superficial, and not fundamental, circumstances) most repugnant to my nature; but given the total antipathy I felt toward marriage, I deemed convent life the least unsuitable and the most honorable I could elect if I were to ensure my salvation. To that end, first (as, finally, the most important) was the matter of all the trivial aspects of my nature ..., such as wishing to live alone, and wishing to have no obligatory occupation to inhibit the freedom of my studies, nor the sounds of a community to intrude upon the peaceful silence of my books.

In his book, Sor Juana: Or the Traps of Faith, (Harvard UP, 1988), Octavio Paz wrote of this momentous act as follows:

Sor Juana expounds a rational decision... The suitable way would have been marriage; the dishonorable, to live unmarried in the world, which, as Calleja [another biographer] says, would have exposed her to being the white wall fouled by men. Juana Inés' choice was not the result of a spiritual crisis or a disappointment in love [as some have argued]. It was a prudent decision consistent with the morality of the age ... The convent was not a ladder toward God but a refuge for a woman who found herself alone in the world.

So Sor Juana, a woman from early modern Mexico, actively chose an intellectual life, a life acquired through her choice to embed herself in a religious community. And it's important to note that though she became a nun, Sor Juana never renounced human contact, often convening gatherings of friends and admirers in the public quarters of the the convent after prayers.

In 1690 Sor Juana was attacked in print by an anonymous figure who was clearly protected and abetted by powerful figures within the Mexican Church hierarchy. She was specifically criticized for devoting herself to the production of secular works to the detriment (or avoidance) of religious subjects. Juana responded in kind, defending herself vigorously and thoughtfully in the Respuesta de Sor Filotea, (which has been called the first feminist manifesto).

In the years preceding her death, Sor Juana came under the firm guidance of her confessor, Father Antonio Núñez de Miranda, (a man who scourged himself with such frequency and severity that the walls and door of his room were spattered with his blood). While Mexico-City society was gripped by severe public health and political crises, it appears that Juana decided to move on from her life as a secular writer and embrace another, less public one.

At this same time she undertook an act which reflected her commitment to change, one which forces me to grimace even now as I imagine it: Sor Juana gave up her library, allowing the great majority of her books and scientific instruments to be dispersed and sold for the benefit of the poor. (Without firm evidence, we are left speculate as to whether this act was forced upon Juana, or was effected without coercion, providing yet another example of her considerable will and determination. However, given her inclinations, coercion seems the most likely explanation.)

Let me just repeat that: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz gave up her library.

She died of disease shortly thereafter.

Sor Juana dazzles, inspires, confounds, and mystifies. As an educator, bibliophile, scholar, and student of the past, I consider her to be someone deserving of the highest honor and respect.

In concluding, I can't improve upon what Octavio Paz wrote in the Epilogue to his book:

As a girl she conceived the idea of disguising herself as a man in order to attend the university; as a young woman she made the decision to enter the convent because otherwise she would not have been able to devote herself to study or to letters. As a mature woman she proclaims again and again in her poems that reason has no gender; defending her inclination towards letters, she composes long lists of famous women writers from antiquity on; she invokes Isis, the mother of wisdom, and the Oracle at Delphi, the prototype of inspiration; she chooses St. Catherine of Alexandria, a learned virgin and martyr, as her favorite saint; she defends her right to secular learning as a preliminary to sacred leaning; she writes that intelligence is not the privilege of men nor is stupidity restricted to women; and, a true historical and political novelty, she advocates the universal education of women, to be imparted by learned women in their homes or in institutions created for that purpose.

Monday, March 06, 2006

Spider-Girl #96

"Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully." Samuel Johnson, quoted by Boswell in his Life of Johnson.

As I've posted earlier, Spider-Girl is facing cancellation at issue #100. If issue #96 is evidence of what's ahead in the remaining books, Spider-Girl will go down on a welcome high note.

In this issue May "Mayday" Parker confronts three problems:

(1) She's consumed with guilt for the serious injury suffered by the fire-fighting father of a friend during a battle in the previous issue. If she had taken the hit, she deduces, Moose's dad wouldn't be in the hospital.

(2) Her principled decision to resign from her high school basketball team has placed coach Flash Thompson's job in jeapardy. In turn, this has strained her relationship with Felicity Hardy, Flash's daughter. (Felicity's mom is Felicia Hardy--yes, that Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat. It's an alternate universe kind of thing; Felicia retired from adventuring, married and divorced Flash T. [and yes, it's that Flash T.], and is presently in a relationship with another woman.)

(3) The Brotherhood of Scriers (an international organization of pallid, ghoulish-looking, murderous fellows in capes) have taken a deep interest in Spider-Girl. This particular problem is greatly compounded by the fact that Kaine, an ally of Spider-Girl who possesses precognitive abilities, has forseen her death at the hands of one of these ghoulish types.

Given all that's in play, (and I haven't mentioned one other sub-plot), this issue could easily have been an utter disaster. However, deft writing, nice characterization, and good art come together to produce pure comic book goodness: secret identity complications; the kind of self-torturing existential guilt that can only afflict young heroes; May's sometime side-kick the Scarlet Spider returns; and, in the final pages, we're given a well-choreographed confrontation with the Scrier who has been shadowing the heroine.

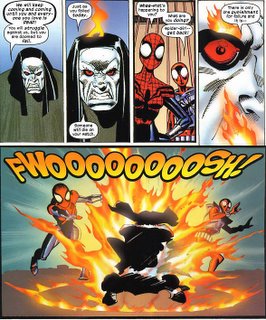

And it must be said that the book's impending demise, coupled with the ongoing Scrier plot-line, places the prospect of the title character's death squarely on the table. After sparring in a martial arts vein, the Scrier ups that ante by brandishing a sword:

Although the attacker's weapon heightens the danger level and puts Mayday off of her game, the tide turns after the Scrier gets the drop on the Scarlet Spider and offers Spider-Girl a choice: she can exchange her own life for that of her friend. This spurs May to put all of her talents to work, and she unleashes a vigorous and welcome beat-down on the villain, with her battle cry being: "No one dies on my watch!"

Though she's right about her friend, Spider-Girl is not entirely right about this. The following panels provide evidence, if anyone needed additional internal proof, that the book is indeed ending soon. The defeated Scrier dramatically pays the ultimate price for failing in his mission:

Like I said, old-fashioned, high-stakes, comic book goodness.

Recent statements by Joe Quesada, editor in chief of Marvel Comics, show no change in the plans about the title's demise. When asked by a Newsarama reader about the possibility of increasing sales through beefed-up advertising, Joe Q. said:

But now, let me ask for a show of hands, how many people on this board right now haven’t heard of Spider-Girl? How many people on this board haven’t heard about how a good book it is? Haven’t heard about the troubles it’s having?

By the way, I’ve asked this same question at convention panels and everyone raises their hands. I’ve asked this at comic shops and everyone is aware of the book, how beloved it is and of course its impending cancellation. Everyone knows about it, everyone knows about its plight, yet it isn’t getting more people to buy it. If everyone knows this, what the heck is an ad going to do for the book? It’s not an awareness problem, I guarantee you that.

There's a small silver lining: I'm thankful that as we enter the final stretch the mind of this reader, and those of the book's creators, are wonderfully concentrated, indeed.

Friday, March 03, 2006

A Catwoman Epiphany

In an earlier post I posed the following questions:

As I was recently reading Ben Morse's "Infinite Crisis: The Secret History" in Wizard #174, an answer came together in my mind. (In that article various talking heads [G. Johns, DiDio, Loeb, Winick, & Rucka] describe how and when they began linking story-arcs together in order to direct readers towards IC.)

I've recently begun to actually consider 52 from the standpoint of meta-level DCU architecture, and I've concluded that if the "big three" are missing for a year, perhaps there's a positive deduction to be drawn from Selina Kyle's being side-lined as Catwoman during that time period, too. From a structural stand-point, Selina's absence might signal something about the character's importance, rather than a simple editorially mandated lowering of her status.

I still stand by what I said earlier about the unease that I have regarding the potential pitfalls that Catwoman's killing of Black Mask and her impending motherhood may pose for her as a heroine operating in the DCU. However, on this single meta-level point, I've come to a more positive conclusion.

It looks to me like Catwoman has been taken down a few pegs, that's for certain. And I do wonder: why would the architects of the DCU believe that to have been necessary? How does that fit in the grand scheme of things?

As I was recently reading Ben Morse's "Infinite Crisis: The Secret History" in Wizard #174, an answer came together in my mind. (In that article various talking heads [G. Johns, DiDio, Loeb, Winick, & Rucka] describe how and when they began linking story-arcs together in order to direct readers towards IC.)

I've recently begun to actually consider 52 from the standpoint of meta-level DCU architecture, and I've concluded that if the "big three" are missing for a year, perhaps there's a positive deduction to be drawn from Selina Kyle's being side-lined as Catwoman during that time period, too. From a structural stand-point, Selina's absence might signal something about the character's importance, rather than a simple editorially mandated lowering of her status.

I still stand by what I said earlier about the unease that I have regarding the potential pitfalls that Catwoman's killing of Black Mask and her impending motherhood may pose for her as a heroine operating in the DCU. However, on this single meta-level point, I've come to a more positive conclusion.

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Good Grief

For the "WTF?/What Fresh Hell Is This?" File:

Adam Liptak, "Prisons Often Shackle Pregnant Inmates in Labor," in today's New York Times.

Essential paragraphs:

What can I say? The thing speaks for itself.

I'm presently away from home, but on my return I intend to communicate with my state and local representatives to inquire about how pregnant incarcerated women are treated in Pennsylvania.

I'll be doing that first thing on Monday morning. Right now, however, I require a very stiff drink.

Adam Liptak, "Prisons Often Shackle Pregnant Inmates in Labor," in today's New York Times.

Essential paragraphs:

Shawanna Nelson, a prisoner at the McPherson Unit in Newport, Ark., had been in labor for more than 12 hours when she arrived at Newport Hospital on Sept. 20, 2003. Ms. Nelson, whose legs were shackled together and who had been given nothing stronger than Tylenol all day, begged, according to court papers, to have the shackles removed.

Though her doctor and two nurses joined in the request, her lawsuit says, the guard in charge of her refused.

"She was shackled all through labor," said Ms. Nelson's lawyer, Cathleen V. Compton. "The doctor who was delivering the baby made them remove the shackles for the actual delivery at the very end."

Despite sporadic complaints and occasional lawsuits, the practice of shackling prisoners in labor continues to be relatively common, state legislators and a human rights group said. Only two states, California and Illinois, have laws forbidding the practice.

The New York Legislature is considering a similar bill. Ms. Nelson's suit, which seeks to ban the use of restraints on Arkansas prisoners during labor and delivery, is to be tried in Little Rock this spring.

What can I say? The thing speaks for itself.

I'm presently away from home, but on my return I intend to communicate with my state and local representatives to inquire about how pregnant incarcerated women are treated in Pennsylvania.

I'll be doing that first thing on Monday morning. Right now, however, I require a very stiff drink.