Tuesday, July 04, 2006

Independence Day, 2006

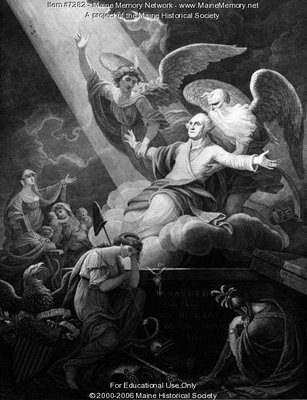

John J. Barralet, Apotheosis of George Washington, 1802.

(Lithograph, the Maine Historical Society.)

Following Washington's death in 1799, many paintings, drawings, and lithographs on the theme of his ascension to paradise were produced. These images are fascinating visual evidence that the revolutionary era was both modern and early modern at the same time.

Rather than take the opportunity to denounce George III and Lord Bute, I'd rather allow a nineteenth-century observer to describe one of the ancillary expressions of independence he discerned in early America.

I was recently re-reading Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America (1835), and was especially struck by chapter 12 of Part III, titled "How the Americans Understand the Equality of Man and Woman." (Pages 705-8 in the Library of America edition, edited by Arthur Goldhammer.)

Now, there's no doubt that this chapter was written by a nineteenth-century European man whose aim was to juxtapose American virtue to European vice. However, though idealized, his interpretation is pretty nuanced nonetheless. (For example, he doesn't argue that there is full equality of the sexes in America.)

Here are several excerpts:

American men consistently demonstrate full confidence in the reasoning abilities of their helpmates and deep respect for their freedom. They deem a woman's mind as capable of discovering the naked truth as a man's and her heart as stalwart in adhering to it, and they have never sought to protect her virtue any more than his behind a shelter of prejudice, ignorance, and fear.

In Europe, where men so readily submit to the despotic sway of women, they nevertheless seem to deny them some of the principle attributes of humankind and look upon them as seductive but incomplete beings. What is most surprising is that European women ultimately come to see themsleves in the same light and are not far from considering it a privilege that they are allowed to seem frivolous, weak, and fearful. American women insist on no such rights. (707)

Thus, Americans do not believe that man and woman have the duty and right to do the same things, but they hold both in the same esteem and regard them as beings of equal value but different destinies. Although they do not ascribe the same form or use to a woman's courage as to a man's, they never doubt her courage; and while they hold that a man and his helpmate should not always use their intelligence and their reason in the same way, at least they believe that a woman's reason is as secure as a man's and her intelligence just as clear.

Americans have thus allowed woman's social inferiority to persist but have done all they could to raise her intellectual and moral level to parity with man, and in this respect they seem to have shown an admirable grasp of the true notion of democratic progress.

... [I]f someone were to ask me what I think is primarily responsible for the singular prosperity and growing power of this people, I would answer that it is the superiority of their women. (708)

If read carefully, Tocqueville's chapter on women serves two purposes: it expertly describes the liberating and pernicious effects of the ideology of separate spheres, while also pointing to how equality of education contains the seeds of enhanced liberation for America's women.